Findings of the 2017-2019 Documentation of Extrajudicial Killings (EJK) committed in the context of the so-called War on Drugs

by the Philippine Human Rights Information Center

Download The Killing State PDF (8 mb)

Part I. Monitoring and Documentation of EJKs

Since Rodrigo Duterte’s inauguration as the 16th president of the Philippines in 2016, the country has witnessed a steep surge in gross violations of human rights. Three years into his presidency, President Duterte’s so-called war on drugs continues without letup, despite his own admission that the drug problem has not been—and cannot be—solved.1

The number of victims continue to mount and the violence and brutality are just as severe. Extrajudicial killings (EJKs) have become the hallmark of the Duterte administration’s governance.

The challenges to human rights organizations are as urgent as ever: to respond to the rise in cases of gross human rights violations, to provide support and intervention to victims and families, to campaign for rule of law and respect for human rights, and to fight against impunity. Among these challenges is the urgent task of documenting the cases of violations, so that they are not erased from public memory, and to gather evidence that could be used for exacting accountability.

PhilRights’ documentation abides by the principles and investigation guidelines set by The Minnesota Protocol on the Investigation of Potentially Unlawful Deaths (2016).2 This document, also known as The Minnesota Protocol, was issued by the Office of the United Nations High Commission for Human Rights (OHCHR) to set international legal standards to prevent unlawful deaths and investigate extra-legal, summary, and arbitrary executions.

The Minnesota Protocol clarifies that a “potentially unlawful death” may (1) have been due to the acts or omission of the State, its organs or agents including law enforcers, paramilitary groups, militias or death squads allegedly “acting under the direction or with the permission or acquiescence of the State,” and “private military or security forces exercising State functions,” (2) have happened when the victim was in detention by or in custody of the State, its organs or agents, and (3) have been due to the failure of the State to fulfill its obligation in protecting life. Under international law, a “potentially unlawful death” is the product of an arbitrary, summary, or extra-legal execution or an alleged extrajudicial killing. In the event that the victim survived the incident, the violation is referred to as “frustrated or attempted extrajudicial killing.”

PhilRights works with community partners in Manila, Caloocan, Malabon, Navotas, Valenzuela, and Quezon City, and the provinces of Bulacan and Rizal for the referral of cases that occurred from July 2016 until the present, for the monitoring of human rights situation in the communities, and for the provision of assistance to victims and their families. The information obtained from the interviews with victims, families, and witnesses are checked against media reports, police records, death certificates, and other sources of information.

How Many Were Killed?

From August 15, 2017 to July 31, 2019, PhilRights documented 118 victims of alleged EJKs.

Demographics

Victims are mostly male adults within the productive age range, are family breadwinners, are low- and irregular-wage earners from the informal sectors of the economy, are of low educational attainment, and are residents of urban poor communities.

Sex, Gender3, and Age

Occupation

Most of them have low-earning jobs.4

The mean daily income of victims with single source of income was Php 425.12, usually earned after engaging in grueling jobs for eight hours or longer. The mean daily income of victims with multiple sources of income (i.e. multiple occupations) was Php 643.75.

Most of the victims, especially those who were construction workers, carpenters, house painters, porters, and electricians, worked on a seasonal basis, earning only when assigned to a project or task. Of the earners, 71 had variable incomes; only 39 were earning fixed incomes.

Those who were self-employed (vendors, tricycle drivers, scavengers) had fluctuating incomes, ranging from Php 300.00 – Php 500.00 a day, depending on their sales or number of trips made.

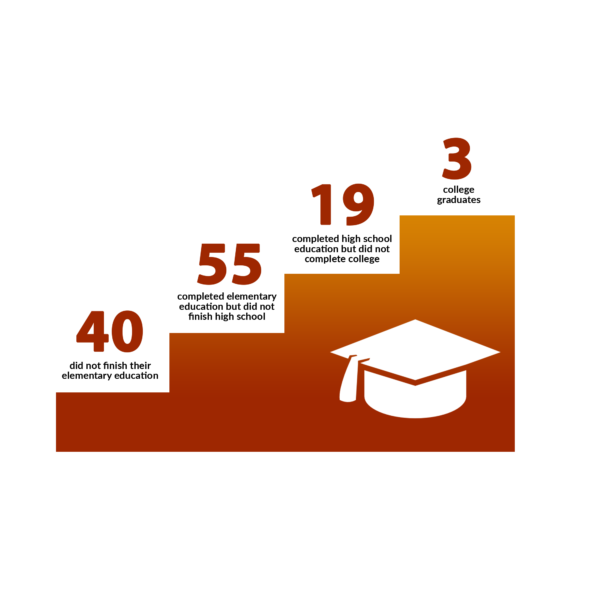

Educational Attainment

Majority of the victims had low educational attainment.

Civil Status

Most of them were not legally married, making it more difficult for their common-law spouses to claim social security benefits.

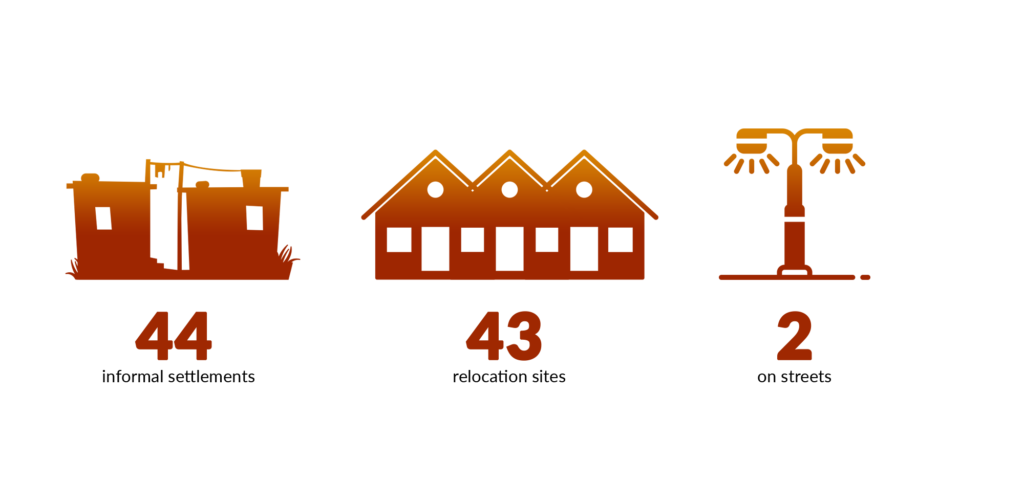

Place of Residence

Most of the victims documented were residents of urban poor communities and did not own their dwelling. Most of them (75.42%) resided in informal settlements, relocation sites, and public thoroughfares (streets).

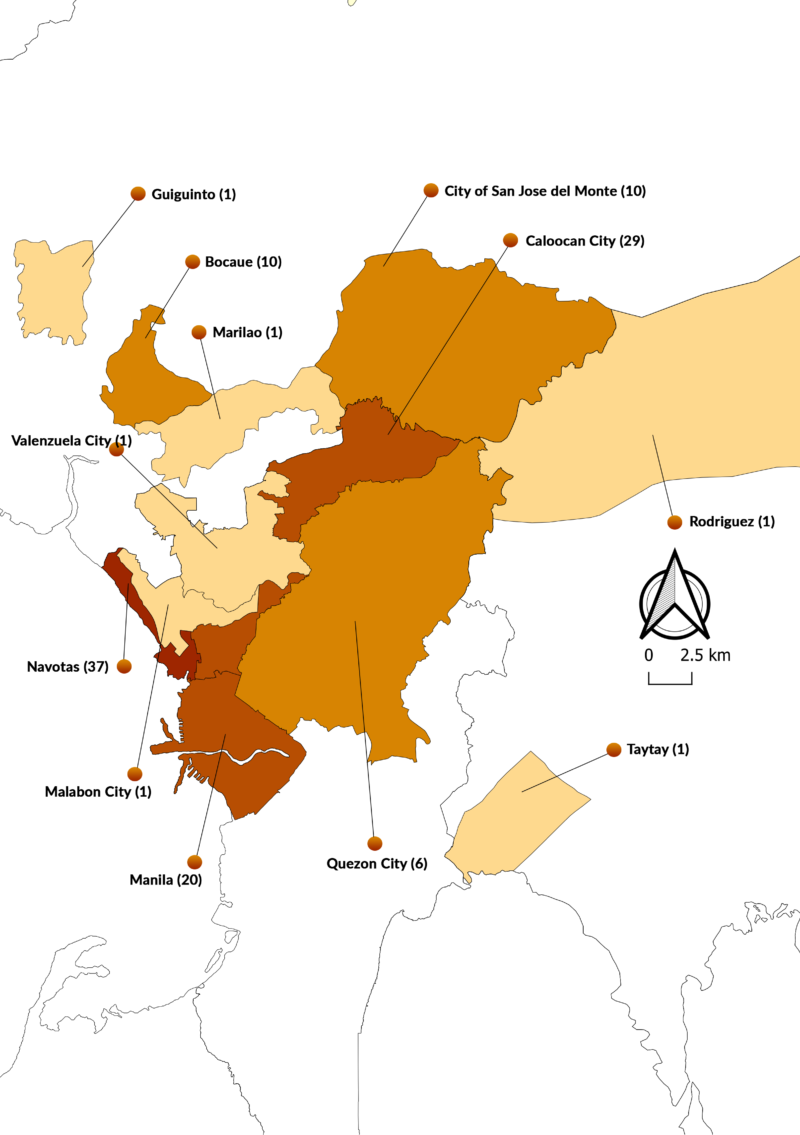

Most of the documented victims lived in Navotas City (31.36%), Caloocan City (24.58%), and Manila (16.10%).5 Caloocan and Manila are also the cities with the highest incidents of alleged extrajudicial killings according to the figures released in July 2018 by the Ateneo Policy Center (APC)6, based on media and online data they collected (Manila, 23.2% of all media-reported extrajudicial killings in the country; and Caloocan, 18.7%). Outside Metro Manila, the City of San Jose del Monte in Bulacan tops the list in the number of victims documented.

CAMANAVA (Caloocan, Malabon, Navotas, and Valenzuela) has a poverty rate of 8.1%7 during the first semester of 2018, 1.5% higher than in 2015, making it the poorest district in Metro Manila.8

Navotas City has some of the poorest communities in Metro Manila. According to the data released by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), the average income of families in the first semester of 2018 was 26.9% below the poverty threshold.9 The poverty gap10 in the city is the highest in Metro Manila, while its severity of poverty is one of highest together with Caloocan City.

In Caloocan City, where the average household income was 30%11 below the poverty threshold in 2018, Bagong Silang and Tala in the northern half of the city registered the highest numbers of documented cases. Bagong Silang is the country’s largest barangay in land area and population, covering more than 524 hectares and with a population of more than 246,000 as of the latest census.12

Most of Bagong Silang’s residents were ‘relocatees’ from Tondo in Manila, barangays along Commonwealth Avenue in Quezon City, and the city of San Juan. Tala covers five barangays with a total population of more than 12,000, based on the 2015 census. Seventeen (17) alleged victims were documented in Bagong Silang and three in Tala.

Recipients of Conditional Cash Transfer

PhilRights also looked into membership with the Conditional Cash Transfer program as an indicator of the victims’ poverty condition.

Thirty-four (34) of the victims had dependents who are beneficiaries of the Philippine government’s Conditional Cash Transfer program.

Without the help of the victims who were the primary income earners, families said that they were left dependent on the small subsidy while struggling to comply with the requirements of the program.

Contribution to Household Income

Fifty (50) (42.02%) were primary income earners, who contributed 51% or above of the total household income.

Dependents

On average, a victim has three dependents.13

Among those left behind, 125 children lost either of their parents. Two (2) children lost both parents.

Alleged Links to Illegal Drugs

Informants were asked whether they had knowledge of the victim’s involvement in illegal drugs (whether as user or “pusher”).

According to informants/families, the nature of the victims’ work was a contributing factor to their drug use and that they were not addicts. Some of the families of the truck drivers, for example, claimed that the victims were using illegal drugs to help them stay awake during long drives.14 Some victims had also been influenced by their co-workers to use illegal drugs.

Some of the documented victims were involved in street-level illegal drugs trade (“pushers”) due to lack of livelihood opportunities. Informants said that earnings from street-level peddling is minimal. Forty-four (44) victims had no known links to illegal drugs.

Informants believe that these victims were killed because of “palit-ulo.” Some were victims of mistaken identity or were killed in operations targeting other persons (“damay”).15

Modalities and Patterns

This analysis also seeks to reveal some of the most striking patterns and modalities of violations, as mined from the details of the incidents, to show when and where the killings usually happen, who the alleged perpetrators are, the common narratives propagated by the official reports, the usual methods of killing, the other violations committed before, during, and after the killing, and other factors that compound the suffering experienced by the families of victims.

When were they killed?16

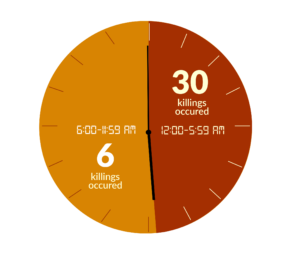

Time of Killing

At least 69 (58.47%) of the documented killings happened between 6 PM and 6 AM.

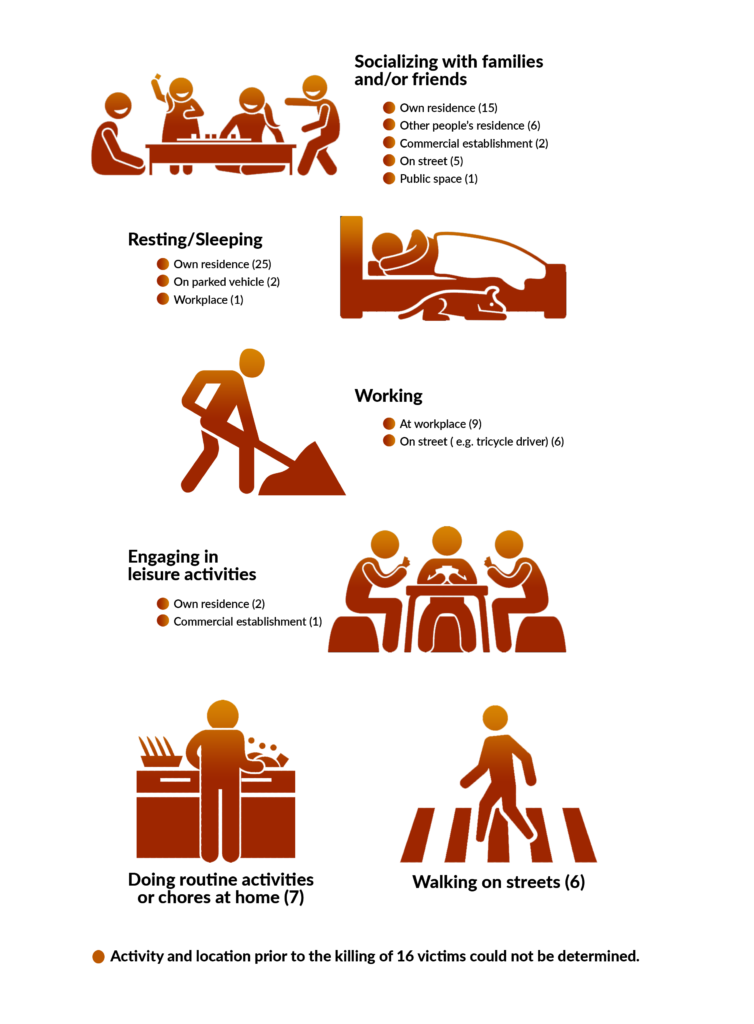

The victims were engaged in routine activities when they were killed: socializing with families and/or friends, working, resting or sleeping, engaging in leisure activities and chores, in transit, in their own or other people’s homes, in workplaces, in commercial establishments, or on the streets.

The victims were engaged in routine activities when they were killed: socializing with families and/or friends, working, resting or sleeping, engaging in leisure activities and chores, in transit, in their own or other people’s homes, in workplaces, in commercial establishments, or on the streets.

Distribution of Documented Killings by City/Municipality

One hundred and seven (107) (90.68%) of the victims were killed within the cities/municipalities where they resided. In Rizal, the lone documented victim was killed in Cainta, a town adjacent to his hometown of Taytay. A victim from Navotas City died while in the custody of Malabon police.

Similar to the geographic clustering of the victims’ place of residence, most of the acts of killing were perpetrated in impoverished areas such as the informal settlements of Tondo (Manila), Malabon, Navotas City, relocation sites of San Jose del Monte City, Navotas City, and Bocaue (Bulacan). In Caloocan City, Bagong Silang and Tala are the red zones for killings.

The location of killings of eighteen (18) victims cannot be ascertained by the informants and families. The victims were either found far from their residence or in funeral parlors: Navotas City (5), Manila (5), Caloocan City (4), City of San Jose del Monte, Bulacan (2), Quezon City (1), Bocaue, Bulacan (1).

Types of Killings According to Alleged Perpetrators

Police Operations and Under Police Custody

Under PhilRights’ documentation, alleged extrajudicial killings are categorized as ‘having occurred during police operations’ if:

a) Police authorities, whether in official uniform or not, introduced themselves as such during the course of the operation b) The police authorities acknowledge (to the media or in official records) that the incident was a police operation.

In comparing narratives, there are contradictions between what the police reports state and what the families say about the conduct of the operations. For example, a case may be reported as a buy-bust operation while the family would assert that the police entered their house without any warrant or sufficient acceptable cause. All of the obtained official reports of police operations conflict with the narratives of the families, from the conduct of operation up to the evidence recovered.

Operations Believed to be Conducted by the Police as Alleged by Informants

Apart from police operations, many killings were also committed under operations by unidentified perpetrators who, informants believe, are police officers. Informants who witnessed the acts of killing claim that the alleged perpetrators are police officers based on their physical attributes and on the witnesses/informants’ familiarity with police authorities operating within their communities. The presence of patrol cars nearby and/or the immediate arrival of police officers after the killing bolster these suspicions.

Operations Conducted by Unidentified Assailants and Riding-in-Tandem Assassins

Another group of alleged perpetrators involves unidentified assailants, killers riding in tandem. The alleged perpetrators of these killings are usually masked and dressed in black or dark-colored clothing. There are also cases with non-police perpetrators who wear civilian clothes and/or do not hide their faces. Majority of the informants and families have stated that they believe that the unidentified assailants have links with State agents. This is congruent to what Amnesty International has revealed in their 2017 report17 where they interviewed hired killers who admitted receiving orders to kill from an active-duty police officer.

Number of Documented Victims by Type of Operation

Types of Incidents by Number of Victims

Eighteen (18) incidents involved multiple victims; these incidents occurred in Caloocan City (7), Navotas City (5), Quezon City (1), Manila (3), Bocaue (1), and San Jose del Monte (1). Due to various factors, including lack of access to informants, not all the victims in these 18 incidents have been documented. PhilRights documented all the fourteen victims of five different incidents.

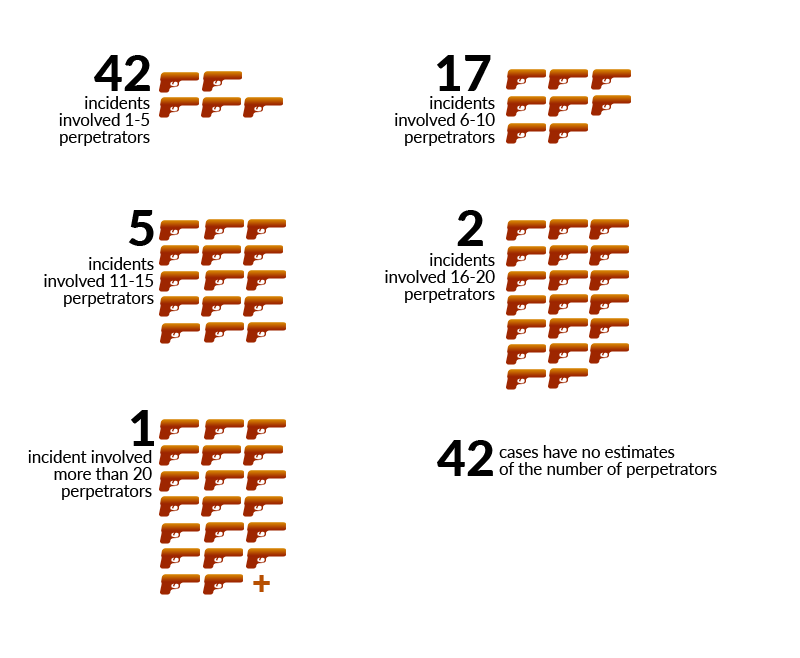

Number of Alleged Perpetrators

Informants for the documented cases (of single-victim killings) report varying numbers of alleged perpetrators, ranging from one perpetrator to over 20, regardless of type.

Note: The total number of incidents is not equal to the number of documented victims because the remaining nine documented victims were killed in five different incidents with multiple victims.

Of those cases with identified numbers of alleged perpetrators, on average, five perpetrators were witnessed as having committed or participated in the conduct of the killings.

Manner of Killing

During the interviews, informants shared what they regard as signs of torture on the bodies of their relatives who were killed in furtherance of the government’s so-called war on drugs.

Twenty four allegedly bore signs of torture. Some of the signs of torture are:

- Beatings and bruises

- Mutilated body parts

- Broken limbs

- Missing fingernails

- Cuts and wounds

- Burn marks

Gunfire Injuries

On average, a victim suffered from three gunfire injuries.

One victim had 18 gunfire injuries; he died in an operation that informants allege was conducted by Manila police officers.

One can argue that the firing of more than one bullet to stop the target from running away or from resisting the arresting police officers is already indicative of undue force.

The use of excessive force is not allowed as stipulated in Rule 7 (Use of Force during Police Operations) of the Revised Philippine National Police Operational Procedures. Rule 7 also specifies the factors to consider in the reasonableness of the force employed, which include the number of aggressors, nature and characteristics of the weapon used, physical condition, size and other circumstances to include the place and location of the assault. Based on the narratives of the informants who were present during the time of killings, the circumstances did not warrant the use of deadly force.

Gunfire injuries are counted individually regardless of whether they are entry or exit wounds.

The figure shows the cumulative number of gunfire injuries per body part to identify which body parts are commonly hit by the alleged perpetrators. Because one victim may sustain multiple gunfire injuries, the total number of gunfire injuries in the above table does not match the number of victims.

Record of Previous Encounter with Law Enforcement Authorities

Arrest and Detention

Forty-three (43) documented incidents involved victims who had records of arrest while 40 of them involved victims who had records of detention. Reasons of past arrests and detention include violations of local ordinances such as loitering, robbery, and drug trafficking.

Tokhang (Knock-and-Ask)-related Record

Twenty (20) incidents involved victims who had been visited by an Oplan Tokhang team composed of police officers knocking on houses and asking the identified drug suspect to surrender.Three victims underwent rehabilitation activities such as Zumba dance exercises.

Drug Watch Record

Nine of the documented victims were in the official drug watchlist. The informants and witnesses themselves have seen the names of the victims in the watchlist, while some were informed by their barangay officials and/or police officers during the conduct of Oplan Tokhang.

Three victims had records of arrest and detention, had encounters with an Oplan Tokhang team, and were included in the official drug watchlist.

Cases with Multiple Acts

Torture

During the interviews, informants shared what they regard as signs of torture on the bodies of their relatives who were killed in furtherance of the government’s so-called War on Drugs.

May torture component. Wala nang mata, pitpit ‘yung kamay, putol ‘yung braso, may mga paso ng sigarilyo. (There were signs of torture. The eyes were missing, a hand was crushed, an arm was broken, and there were cigarette burns.) – KII, LA, Human Rights Defender

Bali po yung kamay tapos , hiniwa at nilagyan ng bala. Pinipilit nilang magsabi. Binanlian pa siya ng kumukulong tubig. Mukhang pinagpapalo pa siya ng tubo. (His hand was fractured, cut and inserted with a bullet. They were forcing him to speak up. He was also scalded with boiling water. It seemed that he was hit with pipes, too.) – FGD, LR, Sampaloc

Tulad nung manugang ni (referring to one of the Community Monitors of PhilRights), tinanggalan ng kuko. (His fingernails were removed.) – KII, SS, Human Rights Defender

Illegal Arrest and Arbitrary Detention

Six victims had been arrested illegally and detained arbitrarily; one of whom was allegedly killed while in detention and one was arrested by the police in the barangay hall where he was brought in for alleged intoxication.

Illegal Search and Ransacking

There were 10 documented incidents of illegal search and ransacking of the house.

Harassment and Threats

Eight victims experienced prior harassment and threats. Some forms of harassment and threats include pointing a gun to the victim and to family members, and death threats if the victims do not obey the alleged perpetrators. Some family members also reported being subjected to sexual harassment.

Bringing the Victims to Other Places

Some of the victims in Navotas City and the City of San Jose del Monte were said to be driven around their cities before being killed. The victims were then brought to secluded places such as grasslands and riverbanks where they were killed.

Personal Properties

Twenty-three (23) victims had their personal properties such as cash and cellular phones missing after the killings, nine of these 23 were killed in police operations.

Some personal properties of 11 victims were confiscated; of these, nine victims had their belongings confiscated by police officers.

The properties of five victims, such as home appliances and furniture, were damaged or destroyed by the alleged perpetrators.

Perceived Irregularities in Processing the Victims’ Bodies

Questionable acts such as the immediate arrival of funeral parlors’ personnel and the bringing of dead bodies to hospitals were also documented. Informants and families assert that these acts are ways for alleged perpetrators to tamper with crime scenes, making it more difficult to collect pristine evidence that will eventually stand up to investigations and court cases.

Sixty-five (65) victims were involved in incidents wherein the funeral parlors were called in by the police officers to collect the bodies, and were immediately present at the site of killing. There were incidents when the Scene of the Crime Operatives (SOCO) and the funeral vehicle arrived together.

Twenty-seven (27) victims were brought to the hospital after being killed; 13 were declared dead-on-arrival. Some of the families questioned the need to bring a victim to the hospital if the death is already confirmed at the site of killing. These sentiments align with a Reuters special report18 that detailed how some hospitals in Quezon City and Manila take in corpses brought by police officers, effectively concealing that the victims were executed.

Denial of Medical Intervention

One victim was denied urgent care and treatment at the hospital due to the inability of the families to pay the hospital bills.

Certification of Death

These are the causes of death, as written, among the available forty-seven (47) death certificates of documented victims:

With erroneous and insufficient details on the causes of deaths, families will find it difficult to use the death certificates as documentary evidence in legal cases.

Extortion by Authorities

Some families reported that they were asked by the SOCO to pay around Php 45,000 before they could retrieve the body. They were told that the payment was for the processing of the body.

Involvement of Funeral Parlors

The surge in killings has been generally beneficial for funeral parlors, especially those that are accredited by the PNP Crime Laboratory.

Sixty-five (65) victims were involved in incidents wherein the funeral parlors were called in by the police officers to collect the bodies, and were immediately present at the sites of killing.

The families of 10 of the victims struggled to pay the services of the funeral parlors; these funeral parlors were allegedly called by the police or were present in the sites of killings immediately after the incidents. On average, families were required to pay around Php 35,000 for funeral services, which may include the transfer of the bodies for processing in funeral parlors preferred by the families, the conduct of poorly done autopsies, embalming, wakes, and burials.

Bullets were still found in two re-autopsied victims. None of the families were provided with the results of the autopsies.

Some informants also described funeral parlors encouraging families to waive their right to demand an autopsy. Others were convinced to allow the death certificate to not state the real cause of death of the victim, and to not use any death-related documents to file cases.

A victim’s family was forced to use a barangay vehicle for the funeral procession after failing to complete the payment demanded by the funeral parlor. Families who failed to complete the payment were often met with various forms of harassment and threats.

Justifications and Narratives of Perpetrators

To justify the use of excessive force and that the killing was indeed necessary, authorities are purveying the self-defense or nanlaban narrative: that the victim initiated the gunfight with the police officers, and that the latter were forced to defend themselves. However, the saturation of the self-defense or nanlaban argument in police reports and resulting media coverage has prompted people to question these claims.

Nineteen (19) victims allegedly engaged in gunfights with the police officers during police operations. The police reports, which were often the main documentary sources of the media for their news reports, state that the victims fired first. The informants, however, assert that these reports are false.

The official narrative is that the victims (1) were involved in illegal drugs and (2) engaged authorities in a shootout. Guns, usually found on or near the victims’ hands, are used as evidence to show that they attacked or fought back. The presence of drugs on the site is used to link the victims to the drug trade.

Despite the claim of the police officers that their operations procedures abide by the law and guidelines, some irregularities have been documented. There were documented cases of police operations where police officers used unofficial vehicles such as unmarked white vans and cars.

Evidence Recovered from the Victims

Most of the informants assert that the evidence found on killing sites did not belong to the victims, saying that the victims were too poor to afford guns. For the police operations and some of the operations believed to be conducted by police officers and by unidentifiable assailants, the informants claimed that the victims were framed and that these pieces of evidence were planted by the perpetrators.

Another modality revealed from the data is the killing of the wrong person either because of mistaken identity or the practice of the ‘palit-ulo’ scheme whereby the victim had been substituted for another target just so the alleged quota requirement could be met. Seven were victims of mistaken identities; three died in police operations, one was killed in an operation believed to be perpetrated by the police officers, and three were killed by alleged vigilantes. Two were victims of the “palit-ulo” scheme in police operations.

Informants believe that in the conduct of the government’s campaign against illegal drugs, shortcuts are employed, resulting in violations of the right to due process. The extrajudicial nature of the killings of individuals suspected by the police as involved in the drug trade show wanton disregard for due process. The execution of individuals upon mere suspicion of involvement in illegal drugs illustrate the impunity by which the right to due process is being violated in the government’s so-called War on Drugs. To accept the claim by the police that most of those killed fought back or nanlaban, which is then used to justify their killing without the benefit of due process, underlines the government’s low regard for the right.

due process, simply underlines the government’s low regard for the right.

Yung right to due processes, automatic na nilalabag ito sa ginagawang pagpatay. Parang sinentensyahan ka na agad kapag na-involve ka sa droga, gumamit ka ng droga, o kaya na-involve ka doon sa pagbebenta ng droga. (The killing itself automatically violated the right to due process. It seems that you are already sentenced of the crime if you happen to be involved in the drug trade, if you are using drugs, or if you are selling drugs.) – KII, GE, Human Rights Defender

Sabi nga namin, ‘yung due process, kung pinaghihinalaan na adik ka, patunayan muna nila dapat na ikaw nga ay adik. Hindi ‘yung diretso patay. Hindi ganon ‘yung proseso dapat. Ang tingin agad sa kanila hindi sila inosente, lahat sila ay kriminal. (As we always say, that with regards to due process, if you are an alleged drug user, they must first prove that you are indeed a user. You cannot be killed right away. The process should not work that way. They were already judged as being criminals.) – KII, HE, Human Rights Defender

Informants shared the view that victims of extrajudicial killings were immediately judged guilty without having been given the chance to prove their innocence. The very nature of extrajudicial killings is seen as contradictory to the right to a fair trial.

Everyone is innocent until proven guilty. Pero dahil nga ang target nila ay papatayin na agad, ‘asan ang fair trial? ‘Yung iba na wala naman talagang kasalanan, lahat ng karapatan binawi na sa kanila kasi kinitil na ang buhay nila. Ang sasabihin, ‘Durugista yan kaya tama lang yan na patayin.’ (Everyone is innocent until proven guilty. When you have perpetrators killing the suspects, where is the fair trial in that? Others were innocent, yet all of their rights were denied because they were already killed. The perpetrators usually say that they are drug users so it’s just right to kill them.’) – KII, LA, Human Rights Defender

Lahat ng mga nasama sa listahan at naging biktima ay gusto sanang lumaban para patunayan na wala silang kasalanan. Pero nandoon na ‘yung pananaw na natatakot sila. Bakit? Eh kasi hindi naman namin alam kung sinong lalapitan. Lalapit ba kami sa pulis? Eh sinong pulis ang pwede naming pagkatiwalaan? At paano pa kami lalaban eh nahusgahan na agad kami? (Everyone in the drug watchlist and who were victimized would want to fight and prove that they are innocent. But they are fearful. Why? Because we do not know where to go. Shall we go to the police? Which police could we trust? And how can we fight if we have already been judged right away?) – FGD, NO, Bulacan

Access to Information

Eighty-seven (87) families found it difficult to gain access to documents, especially police and medico-legal reports.

Some families who requested reports from the police were told that their requests will be rejected because they might these use these documents against the issuing police unit. The families also fear reprisal from the alleged perpetrators if they show any intent to file a case, moreso if they know that the police officers are the alleged perpetrators.

The difficulty of accessing documents hampered the efforts of the families in seeking assistance, often from government agencies and churches that require police reports to validate their assistance requests.

Investigations

Police investigations, which should be mandatory, are rarely done after the incidents.

Only four families were contacted by police for investigation. Most of the families have expressed that they have lost their trust with the justice system.

Some informants allege pressure from the police to name civilian suspects as perpetrators instead of police officers, thereby misleading the investigation. One family was coerced to sign a complaint form that named a civilian as the victim’s killer.

The lack of evidence such as CCTV footage due to being compromised or inaccessible has also been an excuse among investigators to discontinue their investigations. The families themselves find it difficult to obtain copies of these evidence which could be used for filing cases against the perpetrators. Many of the witnesses were also afraid to be documented due to fear of reprisal by the perpetrators.

The investigators and police officers also allegedly discouraged families from filing cases. Some families were told that nothing can be done to the cases of the victims because they are already dead, and that there is no point investigating their cases.

Part II. Other Gross Violations

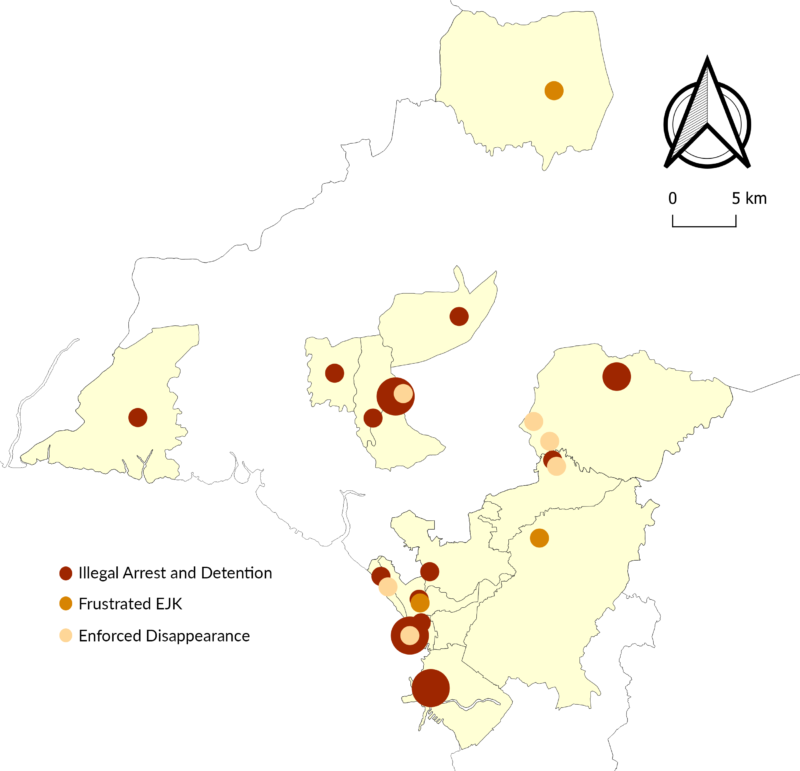

Aside from EJKs, PhilRights has also documented other gross violations such as frustrated EJKs, illegal arrests and arbitrary detention that did not result in death of the victims, and enforced disappearances that happened from May 2016 until July 2019.

Frustrated EJKs

Four victims of alleged frustrated extrajudicial killings were documented. Two victims, together with their families, sought sanctuary for their protection; one of them decided to return to their community. Two victims relocated to the provinces.

Illegal Arrests and Arbitrary Detention

A number of illegal arrests and arbitrary detention have also been documented. Amidst the claim of the government that they have brought the drug suspects before the law through arrests and encouragement of “voluntary surrender,” unlawful acts are still being committed. These acts violate the rights of the accused. An illegal arrest and arbitrary detention is characterized by any of the following:

1. Having no warrant, except for crimes in flagrante delicto

2. Harassment, torture, and sexual abuse

3. Not informing of and disrespecting the Miranda rights of the accused; forcing the accused to self-incriminate or plead guilty of the crime

4. Withholding the necessary information on the cause of arrest and detention and identities of the arresting officers

5. Forcing the accused to give his/her personal information and fingerprints and be taken with mugshots without undergoing the proper procedures

6. Blindfolding and use of improvised handcuff

7. Arresting officers not wearing uniform and without proper identification

8. Improper chain of custody

9. Use of unofficial vehicles

10. Detention without permission to seek legal counsel

11. Extortion

12. Arrest of minor/child below the age of criminal responsibility

13. Other acts not permitted by the police guidelines and by the law

- Twenty-eight (28) of the victims were males

and eight (8) were females. - Six (6) were children (17 years old and below),

seventeen (17) were young adults (18-35 years old),

and eleven were adults (36-59 years old). - The youngest documented victim of illegal arrest and arbitrary detention was only four years old.

Enforced Disappearances

Five alleged victims of enforced disappearance were documented. All five victims have not been found as of this writing.

- Four (4) of the victims were males and

one (1) was a female. - The female was allegedly last seen during a police operation.

- One (1) victim was below 17 years old,

three (3) were young adults (18-35 years old), and one (1) was an adult (36-59 years old)

Instead of being assisted, families of victims of enforced disappearance were often instructed by the police officers they approached to look for their family members in funeral parlors.

Most of the documented cases of illegal arrests and arbitrary detention and enforced disappearances occurred in barangays and municipalities or cities where documented EJKs are also prevalent.

Part III. Assault on Human Rights

The Multidimensional Impacts of Extra Judicial Killings

This section delves deeper into the effects of the killings to civil and political rights (CPR) and economic, social, and cultural rights (ESCR) of families and communities. Fourteen (14) key Informant Interviews (KIIs) on 18 human rights defenders working in communities and civil society organizations, as well as three Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) on 11 families of alleged extrajudicial killing victims from Manila, Navotas City, Caloocan City, City of San Jose del Monte, Bocaue, and Guiguinto were conducted.

Right to Security

The families of four documented victims were illegally arrested and detained after the victims were killed during police operations. Eleven (11) families experienced harassment and threats during and after the incidents.

Even months and years after the incidents, families of alleged extrajudicial killing victims are still experiencing repercussions. In Navotas, several members of three families were arrested and detained with trumped-up charges linked to drugs. As of this writing, Navotas police are still conducting rounds of arrests inside the communities.

In an urban poor community in southern Caloocan City, most of the family members and relatives of an alleged extrajudicial killing victim have already been arrested and detained, leaving many children in their clan without parents to take care of them.

Most of those interviewed see the violation of the right to security beyond the incidents of extrajudicial killings, but also through the perceived sense of insecurity in their homes, particularly for family members who were left behind, and in general, in the communities where most of the killings are happening. They see a violation of the right to security in the pervading sense of fear and the utter absence of a general feeling of personal safety among them.

Hindi na namin nararamdaman na may seguridad pa kami. Hanggang ngayon, kapag may pumasok na pulis sa lugar namin, inaatake ng nerbiyos ang mga magulang ko kasi natatakot sila na baka may patayin na naman. (We no longer feel secure. Until now, whenever there are police officers entering our community, my parents get so nervous, fearing that someone else will get killed.) – FGD, ML, Navotas

Unang-una na nararamdaman nila ay takot. Takot na maulit muli, takot na balikan sila, takot na pati mga anak ay madamay. Takot na sila sa ganong sitwasyon na karamihan ng napapatay ay walang kadahilanan. Kaya para sa kanila hindi na ligtas ‘yung buhay nila. Nawalan na sila ng seguridad. Na kahit sino, bata man o matanda ay pwedeng kitilin ang buhay. (The first thing they feel is fear. There is fear that it will happen again, that even their children will not be spared. They are afraid of the fact that many are killed without cause. For them, their lives have become unsafe. Everyone, whether they are a child or an adult, can be killed.) – KII, CE, Sampaloc, Human Rights Defender

Ngayon, kapag nakakakita kami ng kotseng walang plaka na umiikot sa lugar namin, pasok na kami agad sa loob. (When we see a car without a plate number roaming around here, we immediately go inside the house.) – FGD, JN, Sampaloc

This pervading feeling of insecurity could be felt in the general sense of dread among the families of EJK victims which they attributed to their experiences prior to as well as after their relatives were killed.

Noong nakaburol ang asawa ko, ang daming umiikot na may mga dalang baril. Nakaburol na nga ‘yung asawa ko pero umiikot pa rin sila doon, nagbabantay. Ano pa bang kukunin nila sa asawa ko eh patay na? (A lot of armed men roamed nearby during my husband’s wake. They were observing us. What else do they want when my husband is already dead?) – FGD, AM, Bulacan

May takot pa ring namamayani kasi habang nakaburol ang pinatay na kaanak ay may mga pumupuntang hindi kilalang mga pulis na nakikipaglamay. Anong purpose ng police bakit may ganoon, ‘di ba? Siyempre may nagmamanman kung may mga adik. (We are still afraid because during the wake of a murdered relative, the informant said that there were police officers attending the wake. What is the purpose of that? Of course, they were surveilling if there were drug addicts there.) – KII, SS, Human Rights Defender

The increasing number and frequency of extrajudicial killings in the country resulting from the so-called War on Drugs has created a heightened sense of insecurity in the communities. This is more apparent in PhilRights’ areas of documentation where extrajudicial killings continue to occur.

Nata-tag ang ilang community na pugad ng droga. Iisipin ng mga taong labas na delikado diyan at huwag silang papasok diyan at baka mapagkamalan silang durugista. Kasi ang police kapag pumasok sa isang bahay, kung sino ang kausap ng target nila ay damay na rin. (Communities are being tagged as drug havens. Outsiders would avoid entering these communities, thinking that they will be tagged as drug suspects as well. When police officers enter homes, whomever the targets were associating with also get involved.) – KII, AL, Human Rights Defender

“Dahil nga doon sa mga nangyayari, parang hindi ka na secure doon sa iyong community kasi mismong mga opisyal ng barangay kasama sa mga nang-raid. May takot nang namamayani, nakikiramdam na ang lahat tuwing gabi at hindi na makatulog. May epekto ‘yung halos linggo-linggo ay may pinapatay. (Because of the killings, you no longer feel secure in your own community, because even barangay officials themselves join the raids. There is fear among us; we all become more vigilant at night and we cannot sleep. These are the effects when you have killings almost every week)” – KII, SS, Bulacan, Human Rights Defender

Some families of EJK victims are forced to leave their homes and communities and relocate to other areas or seek temporary sanctuary for fear of incurring further harm from those behind the killing of their relatives.

Yung time po na nabaril ‘yung kuya ko, may bulong-bulungan sa lugar namin na isusunod ‘yung dalawa naming kapatid na lalaki. Kaya ang ginawa namin, kahit nakaburol pa ‘yung kuya ko, napilitan kami na sila ay pauwiin na kaagad ng [redacted]. ‘Yung isa nandito na, nakabalik na. Pero yong isa, pinaalis na namin, pinapunta na namin ng ibang bansa kasi natatakot na talaga kami. (After my brother was shot, there were rumors that our two brothers will also be killed. That was why during my brother’s wake, we were forced to send the other two to [redacted]. One has returned here, but we asked the other to flee the country because we are still fearful.) – FGD, ML, Navotas

Wala na silang kalayaan. Wala ng katahimikan sa puso nila. Ultimo pagtira sa bahay nila hindi na nila magawa kasi mas gugustuhin nilang magtago kesa balik-balikan sila kasi hindi naman natatapos sa pagpatay sa kaanak nila. Binabalik-balikan ang pamilya. May cases na patay na si kuya, nakakulong si ate, nakakulong si bunso, nakakulong si nanay. Iniisa-isa ‘yung mga natitirang kamag-anak. Kaya dahil sa takot ay umaalis na lang sila. (They no longer have freedom. There is no more peace in their hearts. They could not even stay in their homes because they would rather hide elsewhere. The perpetrators keep coming back for them. There were cases of a brother being killed, followed by a sister, the youngest child, or the mother being detained. The perpetrators come after them one after another. The families choose to leave because of this fear.) – KII, LA, Human Rights Defenders

The sudden departure of family members or entire families being hastily uprooted from their homes and communities exact a heavy price on the family’s financial and psychological well-being. Not only do families become physically and emotionally divided, they also have to cope with its concomitant consequences—renting a new house, finding new jobs, and turning their backs from an entire support system that has previously sustained them and their families through the worst of times.

May ilang pamilya kami na pinuntahan na talagang binantayan namin. Umalis sila, lumipat ng probinsya. ‘Yung bahay nila nakatiwangwang lang. Iniisip nila na baka balikan sila. (There are families we have reached out to who have now lef for the provinces. Their houses are now abandoned. They keep thinking that the perpetrators will come back for them.) – KII, CE, Sampaloc, Human Rights Defender

Access to Justice

Beyond just looking at those killed as persons whose right to justice was directly violated, some of those interviewed also believe that the families’ inability to seek and attain justice through the legal system should also be seen as a violation of the right to a fair trial.

Wala kaming nakamit na hustisya diyan. Kahit gusto naming ilaban, di namin mailaban kasi nakatakip yong mga mukha nong mga pumatay. Madaming nakakita na mga kapitbahay na maraming pumasok, na marami sa harap ng bahay namin, pero hindi nila ma-i-describe yong mga mukha dahil nga mga naka-maskara. Kaya kahit gusto namin ilaban, wala kaming magawa. (We have not claimed justice. Even if we wanted to pursue cases, we could not because we could not identify the perpetrators. There were witnesses among our neighbors, but they could not describe the masked perpetrators.) – FGD, ML, Navotas

Yung sa mga pamilya na naiwan, dapat nga sila ang maghabla kasi na-violate ang right to fair trial ng kapamilya nila. Kaso, maghahabol ka pa ba eh wala na? (The families left behind should file cases because the victims were denied their right to a fair trial. But, will they pursue?) – KII, LA, Human Rights Defender

Freedom of Expression

Some of those interviewed felt that the lack or absence of a forum that will allow the families of victims to share and verbalize what they are feeling and experiencing in their current situation leave them with a sense of utter helplessness.

Ang pamilya ng mga napatay imbes na magpahayag ng kanilang tunay na nararamdaman, lalo pa silang tumitiklop, lalo pa silang hindi nagsasalita. Para bang pati sila naniniwala na mali ‘yung ginawa ng kamag-anak nilang napatay. Akala nila wala na silang karapatan na magpahayag ng kanilang nararamdaman, ng kanilang alam, kahit na itinatanggi nang paulit-ulit ng ilan sa kanila na may kinalaman sila at ang kanilang mga pinatay na kaanak sa iligal na droga. (The families, instead of expressing their true feelings, have fallen silent. It is almost like they have become convinced that their killed relatives had done wrong. They believe they no longer have the right to express their feelings, and speak up about what they know, even if they believe that their killed relatives were innocent.) – KII, HE, Human Rights Defender

Most of the families expressed that they no longer know whom to trust within their communities after being tagged as having links with illegal drugs, or due to their feeling of having been betrayed by their neighbors and/or their barangay officials. Other families of victims have started to doubt if there are still people who still care to listen since they feel that their relatives who were killed have already been pre-judged and their entire family tagged as involved in the drug trade.

Hindi ma-express ng mga pamilya ang saloobin nila. Kanino nila i-express? Sa pulis? Eh malamang baka patayin daw sila ng mga pulis. Sa barangay? Eh katulong pa nga daw ‘yung mga iyon minsan. Nagti-testify pa nga daw minsan ang mga iyon para suportahan ang ginagawa ng mga pulis. (The families cannot express their opinions. To whom will they go to speak out? To the police? They believe that the police could also kill them. To the barangay officials? The barangay officials themselves sometimes help the perpetrators. They sometimes testify to support the police.) – KII, LA, HRD

Hindi ka pwedeng mag-voice-out kasi hindi mo nga alam kung sinong pagkakatiwalaan mo. ‘Tsaka sino ba kami? Maliit na tao lang kami kumpara kay Duterte. (You cannot speak out because you do not know whom to trust. Who are we, anyway? We are nobodies compared to Duterte.) – FGD, AM, Bulacan

What appears to be a cause for alarm is when some families and some organizations that support them feel that they need to hide the fact that they are alleged victims of extrajudicial killings just so they can access support services from government agencies. What seems to justify this is the perception that these agencies may be averse to providing support to families for fear of being seen by authorities as not being supportive of the government’s campaign against drugs.

Feeling ng iba sa kanila na wala na silang karapatan. Para silang may sense of guilt. ‘Yung ilang mga natatanong namin, ‘Bakit hindi kayo lumalapit sa amin at sa mga taga-human rights’? Ang kadalasan na sagot nila, ‘Kasi natatakot kami kasi mga human rights organizations kasi kayo’. (Others have felt like they have no rights; they feel guilty. When we ask them why they do not reach out to human rights organizations, they often say that they are afraid to be associated with human rights organizations.) – KII, AA, Human Rights Defender

Freedom of Movement

Freedom of movement recognizes the right of people to travel, reside in, and/or work in any part of the country where one pleases within the limits of respect for the liberty and rights of others. As a general rule, freedom of movement may only be restricted when the restrictions are based on public health, public order, or for safety justifications.

On the other hand, the right to liberty is one of the most fundamental human rights along with the right to life. The right to liberty is the right of all persons to freedom of movement and freedom from arbitrary detention by others.

Families of victims feel that their freedom of movement become compromised when the prevailing climate of fear in their communities restrict them from conducting what used to be regular activities before the incidents of extrajudicial killings escalated in their neighborhoods.

This phenomenon of people and families disappearing or being uprooted drew some comparisons between the Martial Law years under the dictatorship of President Ferdinand Marcos with what is happening now as a consequence of the War on Drugs.

Alas-syete pa lang ng gabi parang ang lungkot na ng pakiramdam mo, ramdam mo na ang lungkot sa lugar. Hindi naman dating ganoon. Maaga pa naman pero pakiramdam mo hating-gabi na. Ang daming napapatay. Ramdam mo sa sarili mo na hindi masaya ‘yung nakikita mong mga tao sa paligid. (By 7 in the evening, you can already feel the fear and sadness in the area. It was not like this before. It is still early but it feels as if it’s already midnight. There are too many killings. You can feel the sadness in everyone.) – KII, SS, Bulacan, Human Rights Defender

In fact, unlike noong Martial Law na ang mga tao ang lumalapit at naghahanap ng refuge o shelter, ngayon, hahanapin mo sila. When I went to Region 4A nong nag-spike ang mga cases doon, hirap kaming hanapin sila. Ayaw nilang lumapit sa Commission on Human Rights out of fear. Ganon din sa Cebu. Nagkawalaan ang ibang tao sa barangay. Iti-trace pa namin. Na-contact din naman namin eventually pero after two months nawala na naman. Kaya it’s a challenge din to EJK work. How do you recover the families? How do you find them? (Unlike during Martial Law when people would come to you to seek refuge or shelter, you now have to search for them. When we went to Region 4A during the height of killings there, we found it difficult to locate families. They did not want to seek help from the Commission on Human Rights out to fear. That is also the case in Cebu. We had traced and contacted the families, but after two months, they disappeared. That’s a challenge to working on EJK cases. How do you recover the families? How do you find them?.) – KII, LR, Human Rights Defender

Right to Health

One of the most palpable consequences of extrajudicial killings is its impact on the overall health of the families left behind. All those interviewed were one in saying that the killings have had a direct adverse effect on both the physical and psychological health of the members of the family.

During the FGDs, the families shared several health challenges that they have to deal with since the killing of their family members.

Sa asawa ko malaki talaga ang pagbabago ng katawan. Umaga palang gin na ang hawak. Hanggang ngayon kakain siya ng kanin pero konti lang. Fifty-seven pa lang siya pero kung titingnan mo siya parang 80 years old na. Ako, hindi rin ganito ang katawan ko, mataba ako dati. Ngayon, wala na akong ganang kumain minsan. Mas lalo na ‘yung mga anak ni [EJK victim], ang papayat. Minsan tinatanong ko, ‘Bakit ang payat mo?’, ang sagot niya, ‘Kasi kung hindi namatay si Papa hindi magkaka-ganito ang buhay namin. Kung hindi namatay si Papa hindi kami ganito’. (My husband’s body has changed a lot. He now drinks gin in the morning. He also would eat very little. He is only 57, but he looks 80 years old. I also used to be bigger. Sometimes, I lose all desire to eat. Even [an EJK victim]’s children, they’ve become so thin. One time I asked them, ‘Why are you so thin?’ One of the children responded, “Because if Papa did not die, our lives would not be like this. If Papa did not die, we would not be like this.) – FGD, SA, Caloocan

Yung pag-iisip ko laging naba-blangko. Lagi ko siyang naiisip. Sa kakaisip ko hindi ako nakakatulog sa gabi. (My thoughts always go blank. I think of him. I hardly sleep at night.) – FGD, LR, Sampaloc

Si Nanay hindi na natutulog sa gabi, sa madaling araw na siya natutulog, tuwing alas-singko ng umaga. Kasi ‘yung mobile (police patrol car) laging doon sa eskinita namin umiikot. Gabi-gabi ‘yun, minsan sa hapon, minsan may araw pa. (Our mother does not sleep at night anymore; she now sleeps at dawn, at 5 in the morning. That is because of the police patrol cars that often roam our alley. That happens every night, sometimes in the afternoon, sometimes even when the sun is still up.) – FGD, JO, Bulacan

Makikita mo kaagad ‘yung epekto sa mga bata. ‘Yung takot, yong phobia, ‘yung kinikimkim na galit lalo na sa mga bata na mismong nakasaksi sa pagpatay. Tapos meron pa na nakapag-asawa na teenager pa yung bata. Namatayan kasi siya ng magulang, ng tatay. Siyempre napakahirap noon at malaki ang epekto nito sa pagkain, sa kanyang pag-aaral, at sa kanilang pamumuhay. Ang escape niya is mag-asawa kasi ang asawa niya ang bubuhay sa kanya. (You can see the effects on the children. The fear, phobia, anger are kept inside especially among the children who witnessed the killings themselves. Then, there was a teenager who cohabitated with a partner right after her father was killed. With a deceased parent, it was really difficult for her, on how she will eat, how she will continue her studies, her daily living. Her escape was to cohabitate with her partner so he can provide for her.) – KII, LA, Human Rights Defender

Of particular concern is the immediate and long-term psychological impact on the children and other family members of victims, especially those who witnessed the actual killings. One interesting insight dealt with how the killings have affected even the reproductive health choices of young people who opted to marry at a young age as a way of dealing with their situation.

Yung mga anak ko parang ayaw nang lumabas nang bahay. Parang ayaw nila na nakikipag-usap sa mga tao. (My children are now afraid to go outside. They seem to avoid talking to people.) – FGD, RE, Caloocan

Ang epekto lalo na sa mga bata ay withdrawal. Nagwi-withdraw sila sa society. May mga maagang manifestation na kung hindi anger, ‘yung kabaliktaran niya na naiipon na galit. Mura nang mura, galit sa lipunan. O hindi magsasalita, ipu-proseso pa talaga ang lahat bago siya magsalita. Ang tendency niyan talaga ay maging violent, aggressive ang behavior. (The effect, especially among children, is withdrawal. They withdraw from society. There are early manifestations of anger, or it’s opposite which is keeping all of that anger inside. They swear a lot, angry at society. Or they do not speak; they process all of their thoughts first before they speak. The tendency is to exhibit violent, aggressive behavior.) – KII, HE, Human Rights Defender

“Parang nagri-rebelde ‘yung mga bata eh. Kung sino na lang minsan sinusugod nila sabay sabi, ‘Ganitong ginawa kay Papa ko.’ Nung nakaraan nga, ‘yung pangatlo [of an EJK victim] nanuntok ng bata. Sabi ko, ‘Huwag ka manuntok.’ Sabi niya, ‘Kasi di ba ganyan din ginawa kay Papa’? ‘Yung apo ko, takot siyang lumabas. Makakita lang siya ng pulis, umiiyak. Nagtatago sa ilalim ng lamesa. (The children seem to become rebellious. Sometimes, they approach people and announce ‘This is what they did to Papa.’ [An EJK victim]’s third child punched another child. I said, ‘Do not punch anyone.’ He said, ‘But that is what they did to Papa.’ My grandson, he is now afraid to go outside. The moment he sees a police officer, he cries. He hides under the table.)” – FGD, SA, Caloocan

Hirap na silang bilhin ang mga pang-maintenance na gamot ng mga magulang, to the point na ‘yung may sakit nalulubog na sa kanyang mga iniindang sakit. (They now find it difficult to buy their maintenance medications, so now their illnesses are getting worse.) – KII, LA, Human Rights Defender

Beyond the immediate consequences on the physical health of the members of the immediate family, there is also the psycho-social trauma they experienced and continue to experience. The expected deep emotional scars that will be left long after the actual killings is a major cause for worry for most of those who were interviewed.

Ang asawa ko ayaw nang magtrabaho mula nang mamatay ang panganay ko. Tapos kapag pinag-usapan ang tungkol doon sa mga anak ko na namatay, sumisigaw ang asawa ko; may trauma ‘tsaka galit. ‘Yung anak kong isa malaki rin ang epekto sa kanya kasi isang beses naghahanap siya ng baril. Parang tanga raw siya na wala siyang nagawa para sa pamilya ng kuya niya. (My husband does not want to work anymore since the death of our firstborn. Whenever we talk about it, he screams; there’s trauma and anger. One of my children was also affected because one time, he was looking for a gun. He feels stupid for not having done anything for his brother’s family. ) – FGD, SA, Caloocan

Lahat ng nararamdaman namin talagang pinalabas nila lahat. Masarap sa pakiramdam. Malaking tulong ‘yun na talagang naibahagi namin sa kanila ‘yung lahat ng sakit na nararamdaman namin. Sa amin grabe talaga ang trauma. (We were guided to let out all of our emotions. It felt good. Sharing with them all of our pain helped us a lot. For us, the trauma was horrible.)” – FGD, ML, Navotas

Others shared how they have been assisted by human rights organizations in processing their trauma.

Huwag lang may dumaan na sasakyan para na kaming mga sira-ulo. ‘Ayan na, ayan na!’ Naging ganon kami diyan sa [redacted]. Parang sa tuwing may sasakyan, ‘Ayan na!’ (When vehicles drive by, we go crazy. “They’re coming, they’re coming,” we yell. This is what we have become here in [redacted].) – KII, VE, Bulacan, Human Rights Defender

Right to Education

Another consequence of extrajudicial killings is the impact on the education of children. With the sudden loss of parents or family members who used to support their studies, some children had to quit school temporarily while others were forced to stop schooling altogether.

Ang apo ko napilitang tumigil sa pag-aaral kasi si [EJK victim] ‘yung nagbibigay dati ng baon doon sa apo ko. Ayaw na rin niya mag-aral. (My grandson stopped going to school because it was his father [EJK victim] father who was supporting him. He also does not want to continue studying anymore.) – FGD, LR, Sampaloc

Kung minsan sabi ng Mama niya, ‘Wala akong mapabaon, wala akong mapakain kaya hindi na lang siya pumapasok sa school.’ (Sometimes the mother tells me, ‘I do not have money for school and I cannot provide for his food, so he stopped attending.’) – FGD, SA, Caloocan

Some children whose families could still afford to send them to school still had to quit schooling while others had a hard time focusing on their studies as a result of the stigma associated with being children of alleged EJK victims. This stigma often resulted in various forms of bullying by their classmates. “Minsan sabi ng Mama nila sa akin, ‘Hindi ko yan pinapasok kasi binu-bully sa eskwelahan. (Once, their mother told me, ‘I do not let them go to school anymore because they get bullied.’)” – FGD, SA, Caloocan

Bukod sa nawalan sila ng suporta, mayroon pang mga nangyayari doon sa school na nagiging dahilan para ayaw na nilang pumasok. Dapat ay pinag-uusapan din sa school ‘yung kalagayan ng mga bata kasi special ‘yung case nila kasi dumadaan sila sa isang matinding crisis. At malaking bahagi ang magagawa ng school diyan kung meron silang appreciation sa epekto ng mga nangyayari sa bata—na hindi lang ito simpleng namatayan, at kung ano ba talaga ang dahilan kung bakit ayaw nang mag-aral. (Other than the loss of parental support, there are incidents in schools that diminish their desire to continue going. The condition of the children should also be discussed in schools because they are going through a terrible crisis. And the school can do a lot more if they have an appreciation of the effects of what happened to the children—that this is not just about losing a loved one—and find out why the children are now refusing to continue studying.) – KII, CL, Human Rights Defender

Most children have a hard time focusing on their studies while dealing internally with the trauma of losing family members.

Nahirapan mag-adjust ‘yung panganay ko. Four months ko siyang binantayan sa school kasi nagwawala siya kasi nakita niya ‘yung pagpatay sa tatay niya. Ayaw niyang magpaiwan. Lagi siyang galit sa mga taong nakakausap niya. Di siya kumakain. Iniiyakan ko siya para lang pumasok. Naiintindihan naman ng mga teachers kung bakit siya nagwawala minsan at bigla na lang tatakbo. Kapag gusto niyang matulog, pinapatulog naman siya doon lang sa labas ng classroom. Basta kailangan nakikita niya daw ako. (My firstborn found it difficult to adjust. I watched over him at school for four months because he would act out, because he witnessed his father being killed. He was always angry with people who talked to him. He refused to eat. I would cry to him just so he would go to school. The teachers did understand why he rages and runs away. When he wanted to sleep in class, he was allowed to take naps outside the classroom. He kept telling me that he needed to see me there.) – FGD, JN, Sampaloc

Nung namatay yong tatay niya, hindi ko alam kung paano ko iku-cover-up ‘yung emotion ng anak ko. Nandon yung na-invite ako ng teacher, ‘yung adviser niya na nagsabi nga sa akin na, ‘Ang laki ng pinagbago ng anak mo mula ng namatay ang Papa niya. Para bang hindi na siya nakakapag-cooperate.’ Kasi matalino ‘yan eh. Lagi siyang may honor. Nung time na y’un parang lagi siyang tahimik. Sinasabi ng teacher na parang wala na siya sa sarili niya. Kaya teacher na rin niya mismo ang nagsabi sa akin na, ‘Give tayo ng break sa kanya. Huwag mo muna papasukin, then kausapin mo siya. I-home study mo na lang muna siya’. Kasi nahihirapan siya eh. (When his father was killed, I did not know how to help my son with his emotions. I was invited by his teacher who told me he has changed a lot since the killing of his father, that he has stopped cooperating. He is a smart kid; he always garnered honors. But during those times, he was always quiet. His teacher told me that he was not himself anymore. That was why his teacher recommended that we give him a break from going to school and to talk to him. Let him study at home. He was having a hard time.) – FGD, AM, Bulacan

Bukod pa doon sa kahihiyan na na-i-impart sa bata, hindi rin siya maka-pokus sa kanyang pag-aaral dahil sa kinategorize ang kanyang ama na masama. So ayon, isa ‘yun sa mga nagiging factor kung bakit ayaw nang pumasok ng bata sa eskwelahan. (Aside from the shame, the child could not focus on his studies because his father was judged a bad person for having been killed. That is one factor why children of EJK victims do not want to go to school anymore.) – KII, LA, Human Rights Defender

Right to Food

The adverse effects on the physical health of family members of victims are often the direct result of the inability to meet the minimum nutritional requirements of the family. With most families belonging to the lowest economic quintile, it can be said that they are no strangers to food insecurity. However, the sudden death of family members who, in most instances are the ones responsible for financially supporting their families, aggravate the food insecurity experienced by the families that are left behind.

“Ang laki ng epekto sa buong pamilya kasi halos ‘yung kakainin nila sa araw-araw ay hindi na nila makuha. (The effect on the family is so great that they cannot even afford enough food for every day.)” – KII, LA, Human Rights Defender

“Hindi ko sila kayang suportahan lahat sa pagkain. Sa mumurahing noodles na lang. Simpleng ulam na galunggong nga lang eh daan din ang inuubos. (I cannot support their meals, except for cheap noodles. Even simple meals of scad fish can already cost hundreds of pesos. )” -FGD, NO, Bulacan

Halimbawa po sa bigas, imbis na makakain ka ng halagang Php 50 na bigas, dadaanin mo na lang sa halagang trenta. Kasi kung sandaan lang pera mo, meron ka nang ulam, meron ka nang bigas. Unlike before na may katuwang ka sa buhay, yong sandaan mo pang-prutas pa lang ‘yun dati. Ngayon, wala ka nang meryenda. Almusal at tanghalian magkasama na. Maghihintay ka na lang ng gabi para makakain ka ng hapunan. Nakakaiyak nga kasi minsan may gustong kainin ‘yung anak mo pero hindi mo maibigay kasi wala kang pera. (In buying rice, for example, instead of getting Php 50 worth of rice, I can only afford to spend Php 30. Because with Php 100, you can only buy viands and rice. Unlike before when I had a partner who helps provide for the family, we could spend Php 100 for fruits alone. Now, we cannot even have snacks. We combine breakfast and lunch into one meal. We wait until dinner for our next meal. I end up crying sometimes because I cannot afford what my children want to eat.) – FGD, AM, Bulacan

The emotional and psychological burden that the remaining adult family members have to deal with as a result of the loss of their kin also affects their ability to fully take on the financial responsibility required to meet the food needs of the family. This is especially the case for grandparents who are suddenly left to support their grandchildren whose parent/s are victims of extrajudicial killings.

Hindi na kagaya dati na sa tamang oras makakakain sila. Kung nagta-trabaho lang sana ‘yung asawa ko, hindi magugutom ang mga apo ko. Parang nawawalan na siya ng gana magtrabaho. Sabi ko, ‘May mga apo ka pa. Kung ayaw mong mag-trabaho, ako ang magtatrabaho. Alagaan mo na lang ang mga bata’. Hindi naman niya kayang alagaan ang mga bata. (It is not the same as before, when the children could eat on time. If only my husband had a job, my grandchildren would not go hungry. He appears to have lost any interest to work. I told him that he still has grandchildren; that if he does not want to work, I will, and he can just look after the children. But he cannot take care of the children.) – FGD, SA, Caloocan

Right to Livelihood

With the heads of the family or the economically productive members of the family mostly being the victims of extrajudicial killings, the capacity of the family to address even its most basic needs become compromised. In turn, this has a direct consequence on the family’s ability to meet their minimum nutritional needs, support the continued schooling of their children, and have the capacity to pay their regular utility bills.

Kadalasan, magulang, tatay, ‘yung panganay na anak na naghahanap-buhay ang napapatay. Kitang-kita mo kaagad ang epekto sa kabuhayan ng naiwang pamilya. (Most often, it is the parents, the fathers, the eldest children who work for the families are the ones killed. You can see immediately the effects to the livelihood of the families left behind.) – KII, LA, Human Rights Defender

Nawalan sila ng katuwang kasi nga halos lahat ng napapatay ay padre de pamilya tapos maliliit pa ‘yung mga anak. Tapos ‘yung mga nanay naman na naiwan, kadalasan ay wala naman talagang stable na trabaho. (They lost a partner who can provide for the family, given that most of the victims were breadwinners and have children who are still small. Most of the wives left behind have no stable jobs.) – KII, CE, Sampaloc, Human Rights Defender

Some of the families interviewed regard the issue of livelihood as problematic even before extrajudicial killings became a major issue in their communities. However, these families also acknowledge that the killing of the most economically productive members of their families have a huge impact on their already challenging financial situation.

“Hindi pa man din na-uso ‘yang EJK, problema na ang kawalan ng kabuhayan dito sa amin. (Even before EJKs became commonplace, the lack of livelihood opportunities was already a problem here.)” – KII, VE, Bulacan, Human Rights Defender

Dati akong lumalabas, nagsa-Saudi ako. [EJK victim] ang pinag-iiwanan ko sa magulang ko ‘tsaka sa dalawang anak ko. Hindi ako ngayon makaalis kasi wala nang titingin sa magulang ko ‘tsaka doon sa dalawang anak ko. (I was working in Saudi Arabia. [EJK victim] was the one taking care of our parents and my two children. Now, I cannot leave for work because no one is going to look after them.) – FGD, ML, Navotas

“Dati hindi ako nangungutang ng puhunan sa paninda ko. Ngayon, nangungutang ako kahit para sa baon ng dalawang bata, at para sa gatas ng mga bata. ( I never needed to borrow money for buying up the goods I sell. Now, I have to borrow money to pay for my children’s schooling and for their milk.)” – FGD, LR, Sampaloc

Right to Social Security

As mentioned earlier, most of the families affected by extrajudicial killings belong to the lowest economic quintile. It does not therefore come as a surprise that a good number of the affected families are recipients of the government’s “Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program.”

The “4Ps Program,” as it is commonly referred to, is a conditional cash transfer (CCT) program administered by the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD). It involves providing cash incentives to families belonging to the lowest economic quintile in return for sending their children to school and for meeting the required number of health check-ups by family members, among other requirements. The CCT is intended to provide basic social security to families who are in most need of financial support due to their economic situation.

When asked how extrajudicial killings affect their right to social security, most of the informants initially said there was minimal effect. However, when other informants mentioned the government’s 4Ps Program, it elicited some insights on how the killings are actually affecting the ability of some beneficiary families to access funds through the CCT.

Nakakaapekto siya somehow sa pagpasok ng mga bata sa eskuwelahan na isa sa mga requirement para patuloy na makatanggap ng suporta mula sa 4Ps ang isang pamilya. Tapos maapektuhan din and kanilang pagiging 4Ps beneficiary kapag si nanay o si pangalan ng grantee sa 4Ps ang na-connect sa droga o napatay o nakulong. (The killing affects the attendance of the children in schools, which is a requirement for the family to continue receiving subsidies from the the 4Ps program. Their status as 4Ps beneficiaries is also affected if the mother or the named grantee has been linked to drugs, or killed, or detained.) – KII, LA, Human Rights Defender

Yung dapat na para sa pag-aaral nung bata ay hindi na sa bata napupunta kundi doon sa interest nung naka-sangla na ATM dahil nabaon na sa utang ang pamilya. (The money intended for the education of the children goes to paying off the interest of the pawned ATM card because they’ve become heavily indebted.) – KII, SS, Bulacan, Human Rights Defender

Nakakahiya mang sabihin, nakasangla ang 4Ps na ATM ng nanay ko. Kasi siyempre, two to three months bago magbigay ang gobyerno so baon na baon na kami sa utang dahil sa mga nagastos sa burol. (As shameful as it is to admit, the 4Ps ATM card of my mother has been pawned off. Since it takes two to three months for the government to deposit funds, we were already heavily in debt because of funeral expenses.) – FGD, NO, Bulacan

Right to Shelter

Shelter is one of our most basic needs. Everyone has a fundamental human right to housing which ensures access to a safe, secure, habitable, and affordable home with freedom from forced eviction.

Right to shelter has always been a thorny issue among urban poor communities as well as for families living in relocation sites. These are the same demographic groups that are most affected by extrajudicial killings.

During the interviews, some informants were able to establish how extrajudicial killings are making an impact on the right to shelter of families left behind. Of particular significance were the insights on how families of victims living in relocation sites are especially vulnerable since most of them still have to pay monthly amortization for their homes and are therefore more susceptible to being evicted should they find themselves unable to continue their monthly payment.

“Nanganganib na ma-eject sila ulit sa relocation na tinitirahan dahil nga hindi na sila nakakabayad ng lote dahil nagkabaon-baon na ang pamilya sa utang resulta sa pagkamatay nang kaanak nila na dating naghahanap-buhay para sa pamilya. Ang mangyayari, ‘yung interest na ipinapatong ni NHA sa utang mo sa lote ay tuloy-tuloy hanggang sa dumating ‘yung time na datnan ka na ng Notice to Evict. At dahil malaki na ang utang mo sa NHA, may posibilidad na maisipan mong ibenta na lang yong lote kasi hindi ka na makabayad at papalayasin ka na rin naman ng NHA. (There is a risk that they will be ejected again from their relocation sites because of their failure to pay, having amassed a lot of debt after the killing of their primary breadwinner. The interest payments continue to accrue until the Notice to Evict arrives. And because the debt to the National Housing Authority is already huge, some families end up considering selling their units since they cannot continue paying for them and they are already in danger of being evicted.)” – KII, SS, Bulacan, Human Rights Defender

Napipilitan silang iwanan ‘yung talagang meron silang bahay at lumipat sa malayo. Siyempre, problema din sa kanila ‘yung paglipat nila. Paano sila makaka-avail ng bahay kung wala naman silang pera? Sinong tatanggap sa kanila kung alam na biktima ng EJK ang kanilang pamilya? Parang kakatakutan ka. (They are forced to leave their houses and move to far-flung places. Of course, the move itself is a problem for them. How could they afford another house if they do not have money? Who will take them on if they are known to be families of EJK victims? They are feared.) – KII, CE, Sampaloc, Human Rights Defender

Another interesting insight was on the inability of families to find suitable housing once they are forced to move out of their homes and communities, given the stigma associated with being part of a family suspected to be involved in illegal drugs.

May isang case sa [redacted] na namatayan siya ng kapatid at asawa tapos nakulong ang isa pa niyang kapatid. From [redacted], dumayo siya ng [redacted] dahil nga ayaw niya na isunod na siya na patayin. Desisyon ng pamilya na pagkalibing nung pinatay nilang kaanak ay aalis at ‘magpapalamig’ na muna siya sa ibang lugar. (There was a case in [redacted] wherein they lost a sibling and a spouse, and then another sibling was arrested. They moved to [redacted] for fear of being killed. The family decided to move away and “cool off” someplace else.) – KII, LA, Human Rights Defender

Part IV. Conclusion

The government’s so-called war on drugs is a war against human rights.

Indeed, human rights violations occurring in the context of this false war can be described as systemic, coordinated, sequential, and comprehensive.

The brutality of killings have sent shockwaves that reverberate across sectors and geographies. The systemic effects of these violations have helped create a climate of fear, resulting in social paralysis. Many victims and families have been kept silent, by choice or by desperate circumstances, thereby depriving the public of a full understanding of the scope and breadth of violations. This, in turn, has paved the way for the unimpeded adoption of more anti-human rights and anti-democractic policies.

The violations appear to be coordinated among these institutions of State power, resulting in interrelated violations that are made possible either by alleged outright collusion of other government agencies and local government units and officials or by looking the other way so that these violations can continue.

The violations can be described as sequential in that an initial violation, by way of an extrajudicial killing, for example, subsequently exposes the family left behind to a host of other violations of their civil and political rights (CPR) and economic, social, and cultural rights (ESCR).

The violations can be described as comprehensive given that the many interrelated CPR and ESCR violations have effects that manifest across most, if not all members of the family left behind, often also unfolding over time to worsening degrees, especially if without the intervention of civil society organizations, religious organizations, and other support groups.

Part V. Recommendations

To the government to put an immediate end to the current campaign against illegal drugs. In its place, the government should take seriously the proposals from various sectors for a public health- and harm reduction-based framework for addressing the drug problem. Consultations with experts on these frameworks are critical in shaping a human rights-based solution to this social ill.

To the President to disavow all his previous statements inciting violence against drug suspects and supporting the excessive use of force in police operations.

To the Philippine National Police to revoke all issuances pertaining to the campaign against illegal drugs which have directly and indirectly led to human rights violations. Also, that all police operations henceforth be guided by principles and standards of international human rights law.

To the Justice department to launch a nationwide investigation into the conduct of the anti-drug campaign and establish accountability, regardless of position and rank, for human rights violations committed. The results of the investigation should guide prosecutors in the filing of appropriate charges for those deemed accountable, regardless of position and rank.

To civil society organizations to further harmonize efforts to document human rights violations and provide support to victims and their families to ensure a more formidable and impactful response. More than ever, all lines of cooperation and collaboration need to be engaged.

To the media, to sustain reporting on the anti-drug campaign and to expand reporting to more meaningfully include the voices and stories of those most affected. Given that media workers are also under threat, to ensure stronger cooperation and identify more areas for dialog to ensure that the important work of bringing accurate information to the public remains viable.

To academic institutions to integrate the study of human rights, its history, concepts, and principles, into the curriculum. This act is key to countering the ongoing distortion of human rights. In the face of worsening human rights conditions, building a human rights culture through the education of our youth is critical.

To research institutions to continue to engage meaningfully with the task of recording, interpreting, and analyzing the many dimensions of this war against human rights. The need for accurate, nuanced, and in-depth information and their popular dissemination is greater than ever.

To the international community to exercise all legitimate means of engagement to influence the Philippine government to put a stop to its campaign against illegal drugs, and more broadly, to compel the Philippine government to honor its obligation that all human rights of all are respected, protected, and fulfilled according to international norms and standards.

To the public to offer support for victims and their families and to assert their rights and remain vigilant against the imposition of anti- human rights and anti-democratic policies.

The war against human rights is a war against all—the people must prevail.

Endnotes