Text and photo by Isaiah Castro

As news stories first reported the election numbers on the evening of May 9, there was a dawning realization of a Marcos Jr. win. Elsewhere, the grip has only begun. “It’s like suffering a nightmare,” a netizen posts, “but one that you cannot wake up from.”

For Martial Law victims, the election results felt like déjà vu—one that can’t help but feel deeply personal. Retired Judge Meinrado Paredes, now in his eighties, was a law student when he was nabbed by the Philippine Constabulary in September 1972, but he recounts the events as if it happened yesterday.

Menmen, as he is fondly called by peers, was a student activist and a key personality in the First Quarter Storm in Cebu during the waning years of the 1960s. He is now convener for the Cebu coalition of the Campaign Against the Return of the Marcoses and Martial Law, which hosted a forum soon after the elections to discuss the significance of, as well as decry, the results.

“The police arrested me early in the morning without telling me why. They only said that I was in a list,” he shared in Cebuano during the forum. Menmen was then a member of the youth group Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan, which was later outlawed with the Kabataang Makabayan and other militant organizations under martial rule.

“We watched carefully where our patrol truck was headed,” he added. “If it made a turn to Apas, then we were going to be held at Camp Lapulapu. But if it went straight to the mountains, delikado nga salvage gyod. [We were likely to be salvaged.]”

Luckily for Menmen, the convoy remained on asphalt to Barangay Apas, where he was incarcerated for months. He would be freed and then arrested again a couple of times after, but would ultimately survive martial rule. The rest of his colleagues were not as fortunate, some of whom have fallen victim to torture or murder either in the cities or the countryside, and Menmen could not help but tear up as he remembers them and calls for the public to “reject and resist” another Marcos presidency.

A Social Media Win

While it may never be truly ascertained whether malfunctioning vote counting machines across the country worked in favor of the now sitting president, the results of the elections was far from what freedom-loving Filipinos had hoped for. A staggering 31 million votes were counted for Marcos Jr. despite him being consistently absent in televised debates and being affronted by controversies surrounding his educational background, estate tax liability, and blatant absence of clear campaign platforms, among many other issues. Leni Robredo, the leading opposition candidate, tailed a far second with just over 14 million votes, less than half of Marcos’ share. If we take the numbers for what they are, the opposition seemed like it never had a fighting chance.

This result seemingly proves not only the pre-election opinion polls favoring Marcos Jr. but also the ever-burgeoning pro-Marcos sentiment in online spaces which several commentators first dismissed as separate and distinct from on-ground numbers. Questions on the family’s true legacy dominated online discussions, at times overwhelmingly, among loyalists and naysayers, academics and laypeople, those who were alive during Martial Law and those who weren’t.

Shrewdly, Marcos Jr.’s political machinery churned content daily, packaged to be as attention-grabbing as possible for audiences through snarky humor, potty language, and a twisted historical spin often bordering on conspiracy.

On Tiktok, Marcos Jr. won “long before voting ended” with meme posts, disinformation, and even fan content generated by real netizens. Millennials and Generation Z consumed stories defamiliarized and recontextualized from existing accounts of the Marcos regime, re-imagined for a contemporary audience hooked on micro-influencer culture. These stories invariably humanized the family, shining a sympathetic light the late dictator’s kin despite the lavish lifestyle they are enjoying in contrast to the regular Filipino.

Joel Ariate Jr. and Miguel Reyes, researchers at the Marcos Regime Research in the University of the Philippines, noted that production of online content to promote the Marcoses spiked as early as over a year before the May polls. Marcos Jr. repeatedly denied employing troll farms to push his case, but studies show, including one sanctioned by academe-led fact-checking group Tsek.ph, that his family is the biggest benefactor of online disinformation, with Robredo as the main target.

“Find me one,” Marcos Jr. challenged those who accuse him of trolling fraud. His detractors would not have to search far. In 2020, Brittany Kaiser, a former employee of the disgraced UK political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica, revealed to news site Rappler that Marcos Jr. himself approached the company to “rebrand” the family’s image on social media—a claim profusely denied by the Marcos camp.

Even decades before Marcos Jr.’s failed bid for the vice-presidency in 2016, myths surrounding the family’s claim to power and source of wealth, attributed to either the Tallano or Yamashita gold, have already sprung up to both deny that they looted the national treasury and spread rumors that the family plans to distribute said wealth.

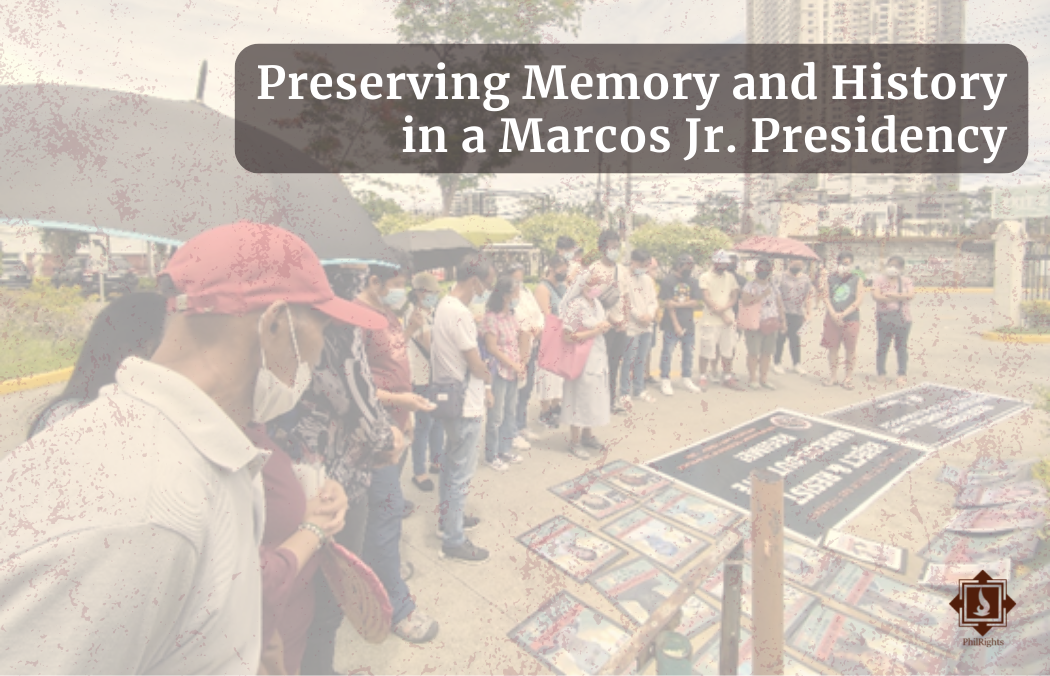

Martial law survivors and kin of martyrs condemn the Marcos win through a prayer and candle lighting activity during a gathering in Cebu City, May 18, 2022.

The Battle for History

This systematic proliferation of propaganda by networked producers is a huge threat to historically established truths as well as an insult to legacy media whose public trust have been systematically eroded in recent years. When lies are repeated and become foundation for further lies, truthtellers come under fire from those who benefit from the spread of falsehoods.

Danilo Arao, associate professor of journalism from the University of the Philippines, believes that since press freedom is a cornerstone of democracy, the struggle for it “should be multi-sectoral in character” among journalists and the larger civil society.

The question of press freedom under a Marcos Jr. presidency already feels more urgent, especially following the National Telecommunications Commission’s move on June 8 to bar public access to websites of organizations critical of government, including small independent news websites Bulatlat and Pinoy Weekly, members of the national Altermidya network, on accusations that they are “communist affiliates” publishing misinformation.

A week later, the Securities and Exchange Commission revoked online news organization Rappler’s operating license over an earlier ruling which affirmed their violation of foreign ownership restrictions. This latest string of attacks also seems like a parting farewell for President Rodrigo Duterte’s hostile treatment of critical journalists, an “abysmal press freedom record” Marcos Jr. should overturn according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

There is also the move to accredit vloggers to join presidential events and Palace press briefings, trading off traditional media ethics for social media metrics and theatrics. Without editorial oversight, these dubious self-styled news organizations and personalities lack standard measures for accountability and are much prone to spreading falsities.

The Threat of Historical Negationism

As soon as a Marcos Jr. win felt imminent, Filipinos online scurried on to hoard primary sources, documents, and films pertaining to the Martial Law years for fear of systemic government seizure. Public concern soared higher when Malacañang’s official website, which also stored the Presidential Museum and Library containing historical records of the Martial Law regime, suddenly went dark a week after the elections. Around the same time, the Bantayog ng mga Bayani website also underwent maintenance, and although the reason for it was not specified, the site’s administrators assured the public that the content of the pages will remain the same.

There is also burgeoning fear that the new president may intensify the purging of books and resources that preserve the country’s experiences with Martial Law. In a Facebook post in May, Alex Paul Monteagudo, director general of the National Intelligence Coordinating Agency, accused publisher Adarna House of “subtly radicalizing” Filipino children against the government when it offered discounts for a bundle of children’s books on Martial Law. The controversial National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) went further, claiming that the publishing house, founded by National Artist Virgilio Almario in 1980, was “infiltrated” by communists.

Several scholars of history and society have argued that conservatism in both education and exposition of true history was instrumental in the return of the Marcoses. The inclusion of factual errors in school textbooks and negligence in educating the youth on the moral and political implications of the elder Marcos regime provided fertile soil for historical manipulation. A study spearheaded by the Far Eastern University Public Policy Center released in January found that discussions of Martial Law in selected Grade 5 and 6 Araling Panlipunan textbooks were fairly limited despite the period’s significance.

In terms of education, Marcos Jr. in his inaugural address had two things to say: first, that there is “hope for a comeback” with Vice President Sara Duterte at its helm, and second, that the learning materials used must be retaught, but he is “not talking about history.” What he means by this is yet to be seen.

Amid these increasingly dangerous prospects, Filipino scholars and educators from higher learning institutions in the country and abroad scramble to assemble a united front vowing to “defend historical truth” against escalating attempts to revise Martial Law narratives and erase “memories of plunder.” There is also an outright movement to denounce the Marcoses’ historical negationism instead of revisionism. According to UP Diliman Professor Emeritus Maria Luisa T. Camagay, historical revisionism is a normal tool in the study of history, involving the reinterpretation of narratives and perspectives when new evidence is uncovered. This should not be confused with historical negationism, which seeks to distort historically established truths through fabrication and forgery of new evidence. New studies are keener on distinguishing the variations between the two.

“We shall seek, not scorn dialogue, listen respectfully to contrary views, be open to suggestions coming from hard thinking and unsparing judgment but always from us, Filipinos. We can trust no one else when it comes to what is best for us,” Marcos Jr. tells 110 million Filipinos, more than half of whom are living in hunger and enduring skyrocketing prices of basic goods, who will be expecting more from him than what is nimbly packaged in his reality television-esque vlog entries. It is up to us to hold him accountable in his promises.

In the face of all of this, the resistance pushes on. The Marcoses won May 2022 with the rallying chant “Bagong Pilipinas, Bagong Mukha,” a rehash from their patriarch’s “Bagong Lipunan” from the 1970s. And perhaps they are right. A nation who forsakes its history is a nation who has lost its soul. An entrenched web of clever social media manipulation, kleptocratic and dynastic politics, and attacks against legitimate media ushered the Marcos family’s return. But the truth does not change. Marcos Sr. was a ruthless dictator. Imelda Marcos was a global laughingstock for her brazen materialism. Their conjugal dictatorship, as per Amnesty International, imprisoned up to 70,000 people, tortured 34,000, and killed at least 3,240.

These are truths not up for question. We remain stalwart for and with those who lost their lives along the way, with those who continue to live with an irreversible experience under tyranny, and with those whose futures are at risk in what may be a return to the darkest, yet bravest, years in our shared history.

Stay informed and join the fight against disinformation. Access and share Bantayog ng mga Bayani’s digital library here.