by Napat Rungsrithananon

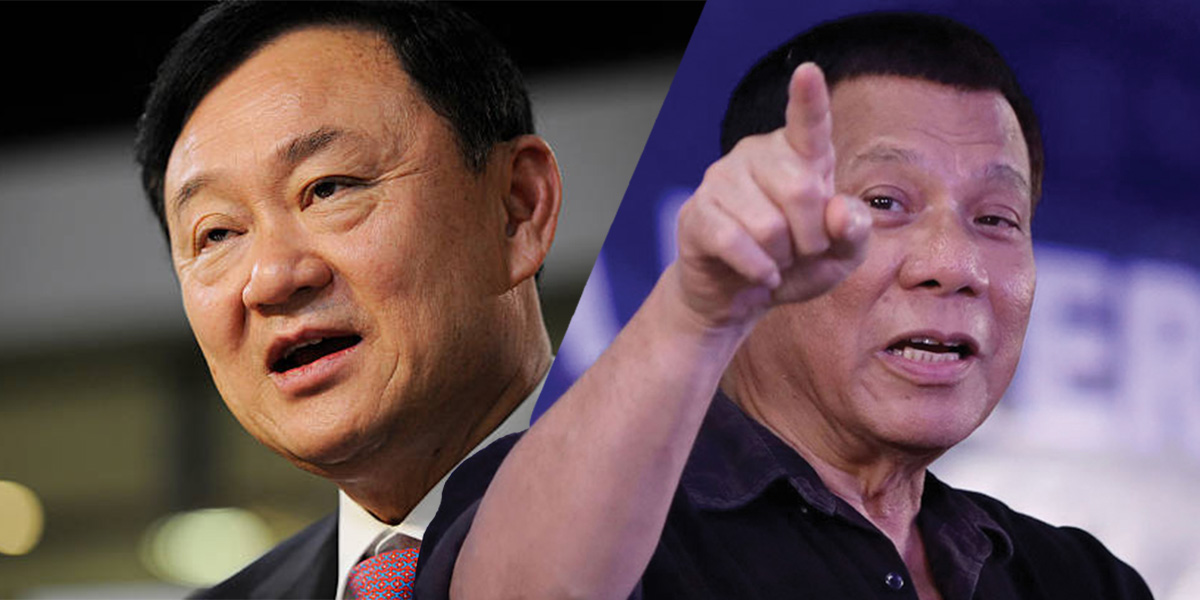

President Rodrigo Duterte came to power in June 2016 after a successful presidential campaign that was heavily dominated by threats to kill tens of thousands of drug criminals. He made it clear that he meant every word of it. In speeches made after his inauguration on 30 June, Duterte firmly reiterated his intention to rid the country of drugs and crime by any means necessary and, in July, made official his infamous so-called ‘war on drugs.’

By July 3—four days after the President was sworn in—the Philippine National Police announced that they had already killed 30 alleged drug dealers. By the end of 2017, Human Rights Watch estimated that more than 12,000 suspected drug users and dealers, mostly from poor families in urban centers across the country, had been killed.

With the bloody crusade still going in full swing, one cannot help but notice that Duterte’s campaign greatly mirrors that of former Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra. The latter began in February 2003 as a response to a boom in methamphetamines—usage of which rose an estimated 2,000% between 1993 and 2001 and overtook heroin as the drug of choice in the country. By 2002, an estimated 2.4% of Thais aged between 12 and 65 were using it.

Thaksin’s campaign racked up the casualties of over 2,800 drug-related deaths—not to mention countless cases of forced disappearances—with over 2,000 deaths recorded in the first three months of the campaign alone. As clichéd as it sounds, the Thai government claims that suspects often fought back and enforcers had to use deadly force to defend themselves.

Besides thousands of casualties, Thaksin’s crackdown also saw rampant human rights violations—including government promotion of violence, countless extrajudicial executions and intimidation of human rights defenders—and breaches of due process by the Royal Thai Police.

Given a striking level of similarity between Duterte’s and Thaksin’s anti-illegal drug campaigns, and given how the latter’s failure has been well-documented and vilified around the world, it would be prudent for the Philippines to pay heed to the experience of Thailand under Thaksin’s war on drugs. Two aspects—or lessons—of the Thaksin’s policy stand out as particularly informative.

“An investigation conducted in 2007 following the overthrow of the Thaksin administration revealed that over half of the 2,800 people killed during the campaign had no links to the drug trade.”

The Collapse of Rule of Law

The first aspect concerns the collapse of rule of law—and an accompanying upsurge in moral corruption—that was triggered by Thaksin’s announcement of the anti-drug campaign. Having urged for his war on drugs to be conducted on the basis of ‘an eye for an eye’ approach and having proclaimed that ‘drug dealers must die,’ Thaksin oversaw Thailand’s sharp deviation from any past and existing effort to promote the rule of law.

Indeed, an investigation conducted in 2007 following the overthrow of the Thaksin administration revealed that over half of the 2,800 people killed during the campaign had no links to the drug trade.

After all, the blacklists—or targets—were widely known to be open to abuse by police and local authorities who sought to settle old disputes. Most names were drawn, for instance, from community meetings, where officials with conflicts could easily and arbitrarily enter names of literally anyone, and the fact that local officials were given a quota of people to report—with additional incentives if they were to exceed—only further undermined the integrity of the lists as well as the whole process.

It comes as no surprise, then, that the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand was constantly flooded with complaints of false arrests, questionable inclusion in drug blacklists and related violations of due process. The first two weeks of the campaign alone, for instance, saw up to 123 complaints alone.

Furthermore, once on the list, the suspects simply had no mechanism to challenge their inclusion, and the only way off was to ‘buy your way off the list, surrender at a police station or end up with a bullet in your head.’

Drugs Won the War

The second notable aspect of Thaksin’s anti-drug campaign concerns its ultimate failure. In other words, Thaksin’s government did not win the war. The crusade failed to deal any significant blow to the drugs network—major Thai drug lords remained generally unaffected, as the infamous blacklists consisted of mostly street- and low-level dealers, while cross-border trafficking continued, as profitable drug routes from Myanmar similarly remained largely intact and protected by the Myanmar and Thai government bureaucracy and business elites.

The demand side of the problem also remained unaddressed. While tough law enforcement is welcome and necessary, one cannot win a war against drugs without looking into demand-side solutions. As long as there continues to be demand for drugs, killings simply will not solve the problem.

“Thaksin’s war on drugs simply failed—that is a well-documented fact.”

The Consequences of Kill Policies

In the short run, it seemed as if the Thai government was making some progress with the killings. In the long run, however, drugs became more expensive, a new mafia came in and officials fell into the corruption temptation. Not only did they fail to deliver the desired results, killings drove drug users further underground and caused methods of consumption to become more dangerous (e.g., individuals switched from smoking to injecting, began to share needles and often subsequently rushed the injections to avoid getting caught) not only for the users themselves but also for the local communities as a whole. The sharing of needles after all led to a spread of HIV and Hepatitis C.

In spite of efforts by the Thaksin administration, drug consumption—especially methamphetamine—ultimately returned to an alarming level. The number of meth labs in Thailand, for instance, went from 2 between 2008 and 2010 to 193 between 2011 and 2012, and the Office of Narcotics Control Board of Thailand seized up to 1,140 kilos of crystal methamphetamine and 9,570 kilos of methamphetamine tablets in 2015 alone.

Even today, Thailand continues to wrestle with the spread of drugs, with key officials openly declaring any past episode of Thailand’s anti-drug policy a failure and now advocating a more pragmatic, integrated and health-orientated approach that includes social measures to alleviate the impact of drug use and dependence by communities.

While it may still be too early to see long-term implications of the anti-drug policy under Duterte, the two alarming aforementioned aspects of Thaksin’s past campaign have already begun to somewhat take shape in the Philippines.

The upholding of rule of law appears to be at stake when an innocent South Korean businessman was abducted from his home, strangled to death at police headquarters and held for ransom under the pretense that he was still alive, and when another innocent 17-year-old high school student was dragged from his family’s sari-sari store and killed execution-style by policemen.

Duterte also appears to have bitten more than he could chew. Having initially declared that he will accomplish his task of ridding the country of crimes and drugs within three to six weeks, Duterte found himself having to readjust his timeframe, first, to one year and then, until the end of his presidency.

Thaksin too exhibited a similar symptom. Having underestimated the complexity and scale of the problem and despite having initially pledged to complete the task in three months, Thaksin was forced to extend the timeframe of his policy again and again. In fact, he ended up waging his failed war all the way until he abruptly left office in 2006.

Thaksin’s war on drugs simply failed—that is a well-documented fact.

So, with the benefit of hindsight, why does the Philippines still want to go down this same route?

About the author: Napat Rungsrithananon currently interns at Free the Slaves. He is based in Bangkok, Thailand. Having previously worked as a management consultant at McKinsey & Company and another boutique strategy consulting firm, Napat is eager to employ his research and analytical skills to pursue his interest in human rights, geopolitics and international development. He also blogs at https://medium.com/humanrights101.