This is the second part of The Killing State: 2019 Philippine Human Rights Situationer, a report released by PhilRights to describe key events in 2019 that have impacted the human rights situation in the country. Here we review the socioeconomic conditions in the Philippines in 2019 and describe the ways in which very little meaningful progress has been achieved in the enjoyment of economic, social, and cultural rights of Filipinos. [Part 1] [Part 3] [Part 4]

by PhilRights Staff

[su_quote]“I can promise you a comfortable life under me. Nakakakain, walang masyadong krimen (not a lot of crime), and drugs—I will suppress it.”[/su_quote]

Two days before the presidential elections in 2016, candidate Rodrigo Duterte issued one last campaign promise before his supporters: A comfortable life for Filipinos.

A quick review of the Philippine economic numbers hints that he may be on the way to fulfilling that promise. The administration reported a 6.4 percent year-on-year growth in the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) during the fourth quarter of 2019. Inflation eased to 0.8 percent in October 2019 compared to the 6.7 all-time high rate recorded in 2018. Year-on-year, Philippine inflation in 2019 settled at 2.5 percent from 5.1 percent in 2018.

In December, the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) also released the government’s official poverty figures for 2018. It estimated poverty incidence among the population at 16.6 percent or 17.6 million Filipinos for 2018. PSA defines poverty incidence as the proportion of poor Filipinos whose per capita income is not sufficient to meet their basic food and non-food needs. The poverty threshold in 2018 is estimated at ₱10,727 on average, for a family of five per month.

Meanwhile, subsistence incidence—the proportion of Filipinos whose income is not enough to meet basic food needs—was rated at 5.2 percent in 2018. The monthly food threshold in 2018 is estimated at ₱7,528 on average, for a family of five per month. PSA compared these results to 2015 numbers, where poverty incidence was at 23.3 percent and subsidence incidence was at 9.1 percent.

Poverty and hunger figures from Social Weather Stations’ (SWS) quarterly Social Weather Surveys in 2019 also paint a generally positive picture. Although self-rated poverty increased in the fourth quarter to a five-year high at 54 percent, or 13.1 million families, 2019’s average self-rated poverty is at 45 percent, still a decrease from the 48 percent recorded in 2018. Self-rated poverty represents the proportion of respondents who rated their family as poor.

The hunger rate in the fourth quarter of 2019 was pegged at 8.8 percent, or 2.1 million families. The annual average hunger rate is 9.3 percent against the 10.8 percent recorded in 2018. The hunger rate represents families who reported experiencing involuntary hunger at least once in the past three months.

The latest employment figures, courtesy of PSA’s preliminary results of the Annual Labor and Employment Estimates for 2019, also suggest improvements. The unemployment rate estimate for 2019 is at 5.1 percent, a small improvement from the 5.3 percent recorded in 2018. Underemployment estimates in 2019 is at 14 percent, declining from 16.4 percent in 2018.

PSA classifies employed persons as belonging to any of these four classes: wage and salary workers; self-employed workers without any paid employee; employers in their own family-operated farm or business; and unpaid family workers. Underemployed persons are defined as those who express the desire to have additional work hours in their present job, or to have an additional job, or to have a new job with longer working hours.

The (Un)Truth in Numbers

Taken at face value, these numbers offer hope that progress is happening. However, there are serious questions about whether these postive numbers translate to better opportunities and better lives for Filipinos.

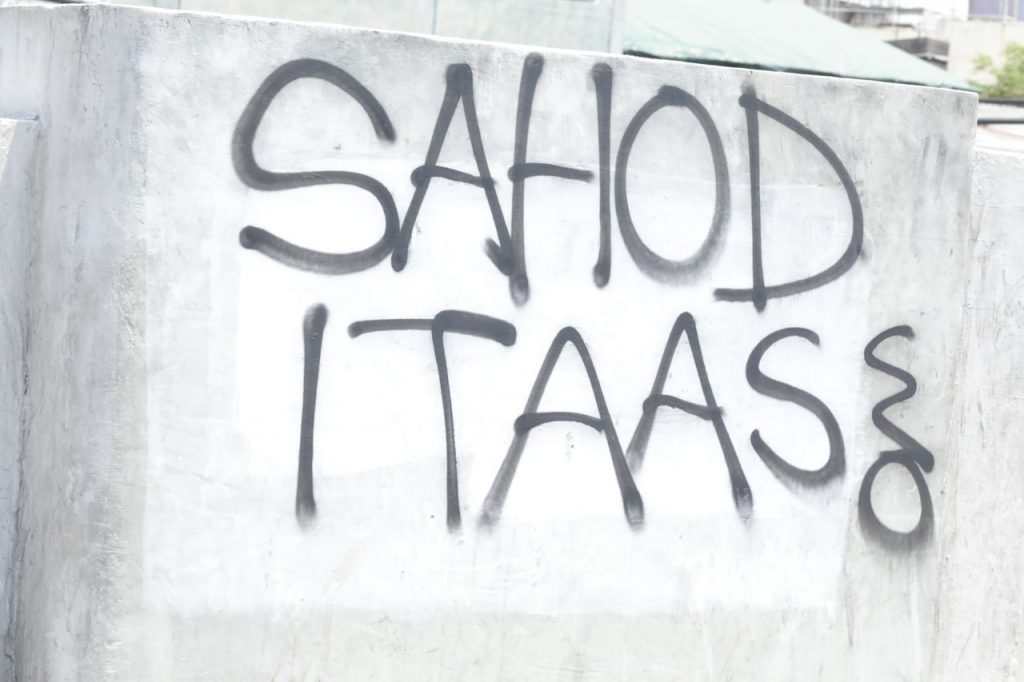

The economic boom, as it were, only worsens inequality in the country as it benefits mostly corporations and oligarchs. As research group IBON pointed out, wages of workers continue to fall in 2019 despite improved labor productivity.

The daily minimum wage rates in the country remain disappointing, going as low as ₱282 in Region I to a high of ₱537 in the National Capital Region. Research by Portugal-based e-commerce site Picodi described the Philippines as one of the worst countries in the world to live in for minimum wage earners. Picodi’s report compared the prices of basic food needs of an adult against the minimum net wages of 54 countries and found that basic food costs amount to 62.3 percent of the minimum net wage in the Philippines. This places the Philippines at 51 among 54 countries reviewed for the report.

A booming economy is also expected to create more and better jobs for Filipinos. However, the country’s economic growth appears to be a jobless one. This idea was echoed in economist JC Punongbayan’s analysis of the country’s economic growth under Pres. Duterte. Punongbayan revealed that only 81,000 jobs were created each year between 2016–2018—way below the annual average jobs created in previous administrations, which are around 500,000 to 800,000.

The government’s declining unemployment figures also remain in question, as it continues to use a 2005 redefinition of unemployment which excludes persons who are“actively seeking work or not seeking work within the last six months upon survey.” This redefinition essentially “stops counting millions of discouraged jobless Filipino workers,” according to IBON.

Indeed, IBON’s own estimate of unemployed Filipinos in October 2019 is at four million, double the government’s two million figure. The group also adds that the few new jobs created were “temporary and poor-quality.”

Anti-Poor Dutertenomics

The Duterte administration’s economic policies and reforms supposedly aimed to improve the lives of Filipinos also appeared to have caused the opposite effect.

For instance, the passage of the Rice Tariffication Law, signed in February 2019, has allowed for the almost unlimited importation of rice. As a consequence, farmgate prices of palay have drastically dropped, hurting the livelihood of local rice farmers. Rice farmers reportedly now sell their produce for as low as ₱17 per kilo, as compared to 2018’s ₱22 per kilo. In provinces like Nueva Ecija, farmgate prices are as low as ₱7 to ₱8 per kilo despite production costs being around ₱12 per kilo. Moreover, the drastic drop in farmgate prices does not translate to lower market prices of rice, meaning that consumers are still affected by high rice prices.

Just like rice farmers, coconut farmers are also hurting from the very low farmgate price of coconut. A Mindanao Times report depicted the downtrend in the buying price of coconut where an already low ₱8 to ₱9 per kilo price level in 2018 plummeted to ₱3.50 in 2019.

The president’s vetoing of the Coconut Farmers and Industry Development Bill and the Philippine Coconut Authority Bill did not make the situation any better for local coconut farmers. These bills were intended to commence the long-delayed distribution of coco levy funds and could have helped ease the burden for the country’s coconut farmers.

Moreover, the deadly anti-drug policy of the government also pushed thousands of families into deeper poverty. Beyond the thousands of deaths, Duterte’s so-called war on drugs has led to multidimensional impacts on the lives of the families of the victims.

PhilRights’ 2019 monitoring and documentation report on extrajudicial killings (EJK) showed that the administration’s so-called drug war does not only violate the civil and political rights (CPR) of the families, but also their economic, social, and cultural rights (ESCR).

The Duterte administration’s approach to ensuring a safe and comfortable life for Filipinos, predicated on a peace and order agenda, instead surfaced a lot of negative consequences for victims of human rights violations: families experienced deteriorating physical and psychological health conditions; children were forced to quit school; and livelihoods were affected, aggravating the food insecurity the families were already experiencing.

Infrastructure development, a priority area for the Duterte administration through its centerpiece program dubbed ‘Build! Build! Build!’, remains beset in controversy.

The New Centennial Water Supply-Kaliwa Dam Project (NCWS-KPD), meant to address the water supply problem in Metro Manila, has been marked with irregularities. The project received flak from indigenous communities, environmental groups, and other concerned civil society organizations because it will displace thousands of indigenous peoples from their ancestral domains—causing the loss of livelihood sources and other basic needs such as food and medicine. Even with the promise of safeguards, indigenous communities also fear the destruction of their sacred lands.

The project also has yet to secure Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) from the indigenous communities in the area. This has not stopped the project to commence, which is a clear violation under the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA). Reports show that half of the access roads to the dam were already built and military were deployed in the area.

Another point against the project is the irreversible damage it will bring to the rich biodiversity of the Sierra Madre mountains. This sparked questions on how the project was granted an Environmental Clearance Certificate (ECC) given the destruction it poses to the environment.

In the president’s mid-term report, he vowed to “ensure that [the tribes’] cultural heritage, rights, and norms are respected and carefully considered.” With the way the project has been railroaded towards implementation, there are serious doubts about the sincerity of these words.

The midpoint of a president’s term is an opportune time to take stock of what has or hasn’t been accomplished. In 2019, the Duterte administration’s socioeconomic policies and programs have achieved very little in terms of genuine improvement in the lives of Filipinos. Despite early promises and a boisterous anti-elite persona, Pres. Duterte has shown himself just as beholden, if not more so, than his predecessors to the interests of the already powerful.

Indeed, it has become increasingly clear that this administration’s approach to economic development has a blinkered view of the relationship between socioeconomic progress and human rights—one that disregards the rights of many for the benefit of a few.

Download the full report [PDF]