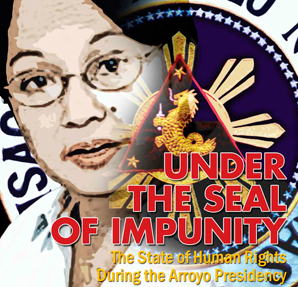

UNDER THE SEAL OF IMPUNITY: The State of Human Rights During the Arroyo Administration

SHE WAS hoisted into power by the grace of a people’s uprising, replacing a president who was booted out of office for corruption.

SHE WAS hoisted into power by the grace of a people’s uprising, replacing a president who was booted out of office for corruption.

In her inaugural address, on January 20, 2001, she outlined her four core beliefs as the nation’s leader: poverty elimination, good governance through improved moral standards, a politics of genuine reform, and leadership by example. She committed herself to “create a fertile ground for good governance based on a sound moral foundation, a philosophy of transparency, and an ethic of effective implementation.”

Most notably missing in that speech was the new president’s human rights agenda. Not a word was said about improving the human rights situation in the country. The absence of any reference to human rights indicated Arroyo’s indifference to the people’s basic rights and foreshadowed her administration’s putrid HR record in the years that followed: the escalation of attacks against HR defenders, lawyers, church workers, journalists, farmers and other basic sectors, done with utter impunity.

Almost nine years after Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo stood on that makeshift stage at the EDSA Shrine, what had become of those core beliefs?

She had more than ample time to fulfill those promises. She was, after all, the longest-staying Malacañang tenant, after Marcos.

Beyond the series of scandals that rocked her administration, Arroyo would be most remembered for her complete failure in combating poverty. In fact, during her tenure, poverty incidence worsened. According to official statistics, the number of poor Filipinos increased by 2 million between 2000 (the year before she took office) and 2006.

Her “new politics of genuine reform” had nothing new or anything reformist about it. She doggedly pursued what her predecessors had done before: automatically appropriate chunks of the national budget for debt servicing to the detriment of social services; push for charter change; open wide the country’s natural resources to foreign plunder.

To prove her “philosophy of transparency”, Arroyo issued, on September 28, 2005, Executive Order 464, requiring “all heads of departments of the Executive Branch of the government” to “secure the consent of the President prior to appearing before either House of Congress.” The EO, which covers officials not only of the executive departments but also the Armed Forces of the Philippines, the Philippine National Police and the National Security Council, was released on the very day that Brig. Gen Francisco Gudani and Lt. Col. Alex Balutan testified in a Senate hearing on the “Hello Garci” scandal. The EO helped in suppressing vital information related not only to the Hello Garci controversy, but also the subsequent scandals and scams such as the fertilizer fund scam, the North Rail controversy and the overpriced NBN-ZTE deal.

Quite a few times, Arroyo’s presidency teetered on the brink of collapse. Scandal upon scandal buffeted her and those very close to her. When the Hello Garci controversy hit the roof, the legitimacy of her presidency was put in question. But she grimly hung on.

As she is about to deliver her last state of the nation address (SONA), this special issue of IN FOCUS takes stock of the performance of Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, 14th president of the republic. — JMVillero

The state of human rights during the Arroyo administration

The state of human rights during the Arroyo administration

Download the In Focus Special Edition Issue No. 9.